Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to discuss the benefits of using sedation in the dental practice.

Expected outcomes

Implant Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz online to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize some history of dental sedation.

- Identify reasons how dental sedation can increase patient comfort.

- Define anterograde amnesia from sedation and how this expands certain patients’ treatment options.

- Realize some reasons to decrease use of local anesthetic.

- Realize how using sedation can combat “compassion fatigue” in the dental office.

Dr. Brian McGue writes about how dental sedation can benefit a dental office, from reducing trauma for patients to helping create a lower stress environment for the dentist and staff.

Dr. Brian McGue discusses how sedation can affect patients and dentists

Sedation of dental patients is not a new concept. Dentists in the United States have been sedating patients for more than 150 years. In the mid-19th century, Horace Wells and William T.G. Morton were dentists who demonstrated that the perioperative use of sedation for dental procedures was beneficial.1 Wells attempted to demonstrate the use of inhaled nitrous oxide as a sedative for a dental extraction at the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1845. Though the sedation Wells performed was not deemed a success, Morton was very successful a year later, again at the Massachusetts General Hospital, while sedating a patient with ether.

At the beginning of the 20th century, sedation of patients for medical procedures became more widespread, and the medical specialty of anesthesiology was created. Technical advances coupled with scientific research and discoveries in pharmacology advanced sedation to become a safer and more predictable procedure. The overwhelming use of sedation, however, was in the field of medicine. Outside the widespread use of intravenous sedation by oral surgeons, dentists generally did not use sedation techniques beyond the use of nitrous oxide for very lightly inhaled anxiety control.

Dentists began to do more sedation in the 1990s when oral conscious sedation began to become popular.2 The use of an orally administered sedative pre- or peri-operatively became widespread for dentists to alleviate anxiety during dental procedures. The nature of current dental practice appears to be evolving to a more surgical focus with the accelerated use of implants. With this evolution, the use of sedation has become prevalent as dentists strive to make their patients more comfortable during these surgical procedures.

The increased use of sedation by dentists can be attributed to many factors. Some of these factors are obvious and some are not. This article will try to address some of these reasons.

Why do we sedate patients?

Patient anxiety and comfort

Patient anxiety and comfort are the most obvious reasons for sedation. The American Dental Association estimates that 100 million Americans do not seek dental care.3 Severe debilitating fear of the dentist has been estimated to prevent 60 million people from entering a dental office. Sedation is a method for lowering this barrier and permits patients to receive dental treatment. If a dentist is attempting to build a patient base, this group of patients can be an aid in that endeavor.

Patients also have fear of specific dental procedures. The fear of some of these procedures can be understood. Third molar removals, implant procedures, multiple extractions, endodontic procedures, etc., can involve complex procedures, loud sounds, unpleasant sensations, and disconcerting instrumentation that can elevate a patient’s negative perceptions. However, the fear of some other procedures may not be as well understood by dental practitioners. From personal experience in my practice, two patients that we perform dental prophylaxis on every 6 months request sedation. Though many dental team members perceive receiving dental prophylaxis as a non-stressful, pleasant experience, there is a segment of the population that feels a sense of foreboding when they consider their routine dental prophylaxis.

Additionally, it may not be simply fear of a dental procedure that keeps a patient from seeking care — it may be the fear of sitting still for an extended length of time. Sitting in a dental chair with one’s mouth open for an extended time may be a source of stress for some people. Sedation helps with this because many of the sedation medications used in the dental office can cause the sensation of time compression. A 2-hour procedure can feel like a 15-minute procedure for a sedated patient.

Primum non nocere (First do no harm)

As health care providers, we have an ethical responsibility to not harm a patient. Iatrogenic injuries can occur in the dental office — most dental practitioners have inadvertently caused a minor injury to a patient. Nicking a tongue with a bur, retracting a patient’s cheek too aggressively, or having a tissue flap tear while reflecting are all examples of minor injuries that can occur but most likely do not have any long-term effects. Some injuries though are not obvious or even physical.

Mental trauma can occur from dental treatment. As mentioned before, dental procedures, even procedures that appear non-threatening, can create a lot of anxiety for patients. Most dentists can relate to having to manage an extremely fearful patient who had a previous negative dental experience. As dentists, it behooves us not to be the practitioner who created the negative experience that so traumatized a patient that he/she avoided dental care for years.

Anterograde amnesia

The primary class of medications used in sedation dentistry is benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines are known to cause anterograde amnesia. Anterograde amnesia is the loss of memory of during the time the patient is under the influence of a certain medication. Patients simply don’t remember the procedure for which they were sedated. Many patients are happy with not having memory of the procedure. This type of patient arrives for the appointment, goes to “sleep,” and “wakes” up after the procedure is concluded. Almost all sedations done in dental offices are conscious sedations where the patient is awake and responsive so the patients are not asleep even though many think they were.

Anterograde amnesia can be a practice builder. If a patient has a painful tooth, and the dentist is able to sedate them, do an endodontic procedure, and a CAD/CAM crown during the sedation, the patient can emerge from the sedation with an asymptomatic white tooth. These patients will tell other potential patients about their positive experience and help build your practice.

Decreased use of local anesthetic

When we train dentists to perform sedations, we encourage the use of online services that check the patient’s own medications against the administered sedation medications for interactions and also the local anesthetics we are intending to use on the patients. Many of the attendees at our courses are surprised by the lack of interactions with sedation medications but are more astonished by the significantly higher number of interactions between the patient’s medications and the local anesthetics.

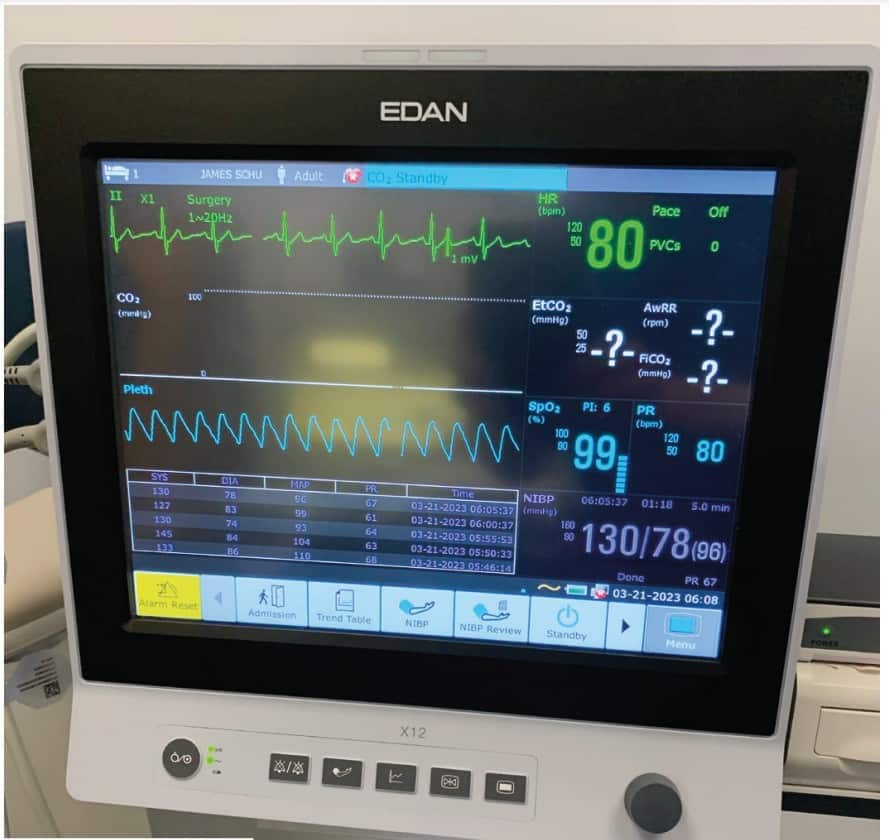

Many local anesthetics are vasoconstrictors and can cause an increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Physiologically, these changes can be detrimental to the patient and can precipitate a medical crisis. As dentists, one of our goals in treating patients is to try to reduce inherent risks for the patient. Sedation is one method of lowering how much local anesthetic we are required to use to properly anesthetize a patient for a procedure.

An article written by J.B. Murray in the Journal of Psychology in 19714 looked at decades of psychological research and was able to definitively conclude from his research that apprehensive patients have a lowered threshold of pain. In other words, a nervous patient will feel pain quicker and at lower stimulus levels then a non-anxious patient. As dentists, we already inherently know this. In the dental chair, it is the nervous patient that is harder to numb.

Prior to Murray’s article, there had already been connections made between the perception of pain and apprehension. In his 1960 book, Pyschophysiologic Approach in Medical Practice, William Schottstraedt5 theorized that pain and apprehension have a circular relationship. Pain causes apprehension, apprehension heightens one’s perception of pain, which then causes more apprehension.

If we can break the chain of apprehension through sedation, then we can lower the patient’s perception of pain, and thus, use less local anesthetic.

courses offer a way to expand technical skills.

Higher quality of dentistry

Can the patient’s behavior negatively impact the quality of dentistry a dentist is trying to provide? As dentists, we all will answer “yes” to this question. We have all had the apprehensive patient who will not listen to our instructions, sit still during the procedure, and/or be overly dramatic when they perceive they’ve felt something.

By removing a patient’s negative behavior from the equation, the dental team can focus on the technical aspects of the procedure. One can equate this to placing an isolation device to get better visualization on the area we are treating. Another analogy is using a surgical guide to place an implant. The guide is just another tool we can pull off of our shelf in order to increase the level of the quality of dentistry we are providing. Similarly, sedation simply can be another tool to remove factors that may interfere with the quality of treatment.

Sedation enables the dental practitioner to perform and learn higher levels of dentistry

The profession of dentistry is unique and amazing. One of the reasons for this is the ability to continually expand and refine one’s clinical skills throughout a career. Very few professions are geared in this way. Continuing education courses offer a way to expand technical skills that can be honed with continued use of those new skills in practice.

Sedation is a tool that can be used in order to relax the patient, take their behavior out of the equation, and let the dental team focus on learning and refining these new skills. It has been said that “repetition is the moniker of learning.” Sedation is one way to have those early repetitions be in a lower stress environment for both the practitioner and the patient. This allows the dental team to focus on what they are learning in the early stages of their development.

Learning these higher levels of dental treatment is a win-win for both dentist and patient. For dentists, it can combat job burnout, promote long-term job satisfaction, and allow dentists to treat patients in a more comprehensive way. For patients, having the dentist able to perform higher levels of dentistry is advantageous because they can have most of their dental work done in one office and have more dentistry done in one appointment which helps them avoid multiple days off of work.

Compassion fatigue

Compassion fatigue is a clinical term that is applied to health care workers, educators, first responders, members of the clergy, and funeral home workers.6 For health care workers, there is a clear definition of compassion fatigue:

“The ‘cost of caring’ for others in emotional or physical pain. Defined as occupational burnout in conjunction with vicarious traumatic stress, which is caused by indirect exposure to stress. Finding emotional energy to calm and reassure apprehensive patients and maintain a confident demeanor while your patient is exhibiting fear or panic can be draining. The potential for negative energy transfer is substantial. Health care workers are generally very sympathetic and empathetic toward others. That is why they are in health care.”7

As dentists, we have all probably experience compassion fatigue at some point. I like to make the analogy that we all start the day with a large vat of compassion. Throughout the day, we ladle out compassion to whomever needs it. Eventually, toward the end of a long day at the dental office, the vat is dry. We leave the office and arrive home to our spouses, children, and/or pets, and many of them also want some love or compassion. Unfortunately, at this time of the day, the vat may be empty. Unchecked compassion fatigue can create burn-out, exhaustion, and mental illness.

Sedation can dramatically lower the amount of compassion a dental team has to ladle out because sedated patients are much less anxious.

Conclusion

Dentists have been sedating patients in their offices for a long time. In fact, in the early history of sedation and anesthesia, dentists were at the forefront of its development. In today’s modern dental practice, sedation has become widely used. For many dentists, it is a way to build a practice, expand their skills, and decrease their own stress level. The science of sedation will continue to evolve and most likely help to expand the options in the dental office.

Dental sedation is one way to reduce patient trauma in the endodontic office. Read how Drs. S.K. El-Ebrashi and J.M. Burstein, and Mr E. Mazone worked with a patient with high dental anxiety to provide him with a prosthesis. https://implantpracticeus.com/rehabilitation-of-a-severely-dental-phobic-patient-with-a-maxillary-removable-prosthesis-and-a-mandibular-fixed-detachable-hybrid-prosthesis/

References

- American Society of Dental Anesthesiologists. History. https://www.asda.org/about-us-2/. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Donaldson M, Gizzarelli G, Chanpong B. Oral sedation: a primer on anxiolysis for the adult patient. Anesth Prog. 2007 Fall;54(3):118-128; quiz 129.

- Beaton L, Freeman R, Humphris G. Why are people afraid of the dentist? Observations and explanations. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23(4):295-301.

- Murray JB. Psychology of the pain experience. J Psychol. 1971 Jul;78(2d Half):193-206.

- Schottstaedt, W. W. Psychophysiologic approach in medical practice. Chicago: The Year Book Publishers; 1960.

- Cocker F, Joss N. Compassion Fatigue among Healthcare, Emergency and Community Service Workers: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016 Jun 22;13(6):618.

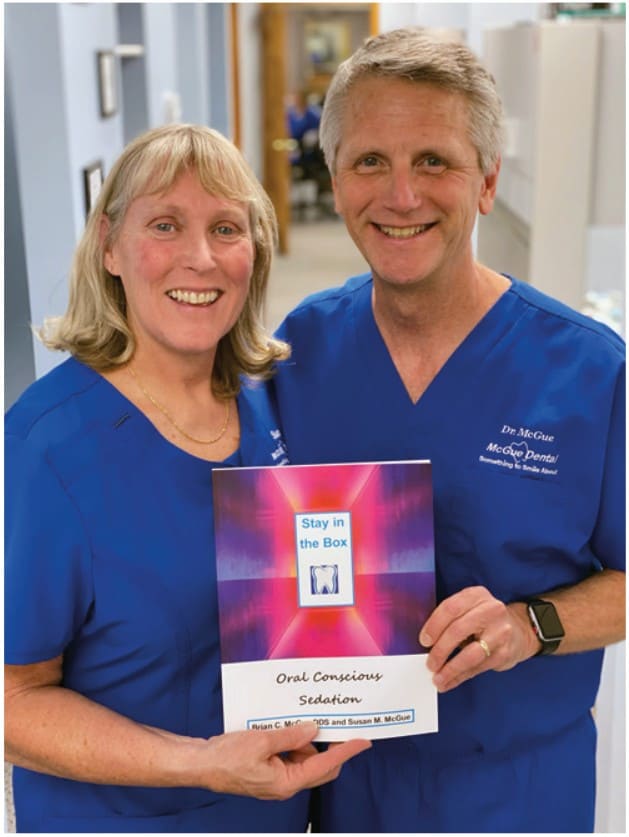

- McGue, BC, Susan M. Oral Conscious Sedation. Stay in the Box Sedation [Course Manual]. 2021;(1), 4-5.

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Brian McGue, DDS, is a fulltime practicing general dentist with a private practice in Chesterton, Indiana. His practice has a comprehensive focus offering a variety of restorative and surgical treatments with an emphasis on full-mouth rehabilitation while using sedation for patient comfort. Dr. McGue and his wife, Susan, lecture on the topic of sedation and run hands-on workshops for dentists interested in incorporating oral and IV sedation into their practices at The Pathway in Tempe, Arizona (www.thepathway.com) and the 3-D Dentists facility in Raleigh, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee (www.3d-dentists.com). Together they have authored three textbook manuals on sedation. Dr. McGue is a fellow of the Academy of General Dentistry and a member of the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology, the International Anesthesia Research Society, and an educational member of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Dr. McGue and Susan McGue can be reached at stayintheboxsedation@gmail.com.

Brian McGue, DDS, is a fulltime practicing general dentist with a private practice in Chesterton, Indiana. His practice has a comprehensive focus offering a variety of restorative and surgical treatments with an emphasis on full-mouth rehabilitation while using sedation for patient comfort. Dr. McGue and his wife, Susan, lecture on the topic of sedation and run hands-on workshops for dentists interested in incorporating oral and IV sedation into their practices at The Pathway in Tempe, Arizona (www.thepathway.com) and the 3-D Dentists facility in Raleigh, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee (www.3d-dentists.com). Together they have authored three textbook manuals on sedation. Dr. McGue is a fellow of the Academy of General Dentistry and a member of the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology, the International Anesthesia Research Society, and an educational member of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Dr. McGue and Susan McGue can be reached at stayintheboxsedation@gmail.com.