Drs. S.K. El-Ebrashi and J.M. Burstein, and Mr E. Mazone show a collaborative effort to provide a patient who has dental anxiety with maxillary and mandibular prostheses.

Drs. S.K. El-Ebrashi and J.M. Burstein, and Mr. E. Mazone illustrate a collaborative effort while treating a patient with high dental anxiety

Introduction

This clinical report demonstrates the management of a patient with dental anxiety and dental phobia due to a traumatic experience at the dentist as a child, in which a single-surgery approach was used and no local anesthetic for future appointments. The management of the patient was performed at the ClearChoice Dental Implant Center in Portland, Oregon. The entire dental team, lab, and staff were together in the same center, making the process collaborative, efficient, and helpful in managing the patient’s dental anxiety and phobia.

Traumatic dental experiences can make patients reluctant to seek care

Many patients have had traumatic dental experiences as children, making them reluctant to pursue future dental treatment.1 Psychosocial factors that prevent patients from accessing dental care include their education levels, socioeconomic status, age, gender, ethnicity, dental anxiety, and perceived vulnerability.2 High dental anxiety may be the primary reason patients do not pursue dental treatment.3

Humans learn by conditioning

There are techniques for helping patients overcome their dental anxiety. Hypnosis maybe useful for some patients.4 Systematic desensitization is another approach used to gradually expose new procedures to calm a patient’s anxiety.5 Managing patients who are truly dental-phobic requires the use of a calming manner, anxiolytic medications prior to dental treatment, and intravenous medications for sedation during surgery.

Clinical report

A 40-year-old male patient presented to our clinic with a chief complaint of pain and embarrassment of his appearance. The patient hadn’t seen the dentist in more than 20 years and had many infected and broken teeth.

Medical history was nonsignificant. Vital signs were normal.

Examination

The patient was not under the care of a physician. He was extremely anxious regarding any dental appointments and was very needle-phobic.

Extraoral examination

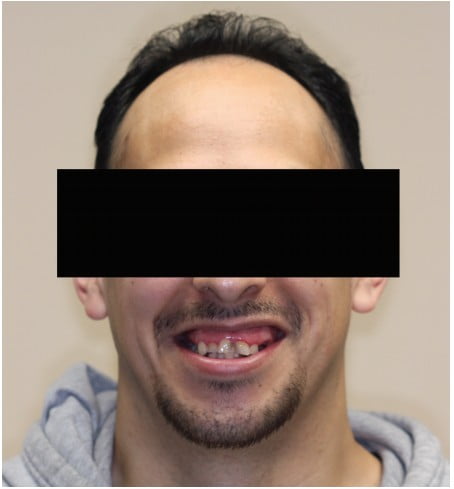

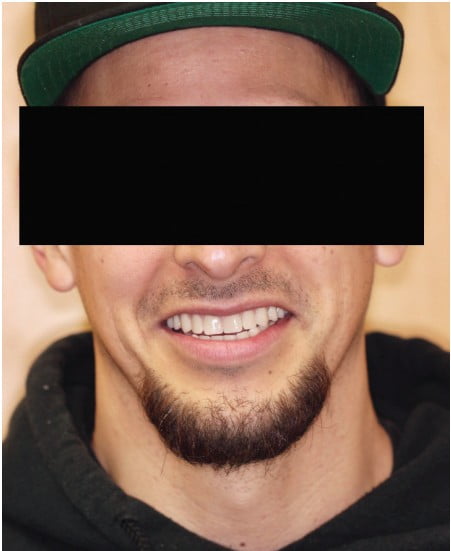

The extraoral examination revealed a symmetrical face with a short upper lip (Figure 1). The patient had a gummy smile with significant exposure of maxillary gingival tissues (Figure 2). His range of motion and opening were normal, and no abnormality was detected with the temporomandibular joints or muscles of mastication.

Intraoral examination

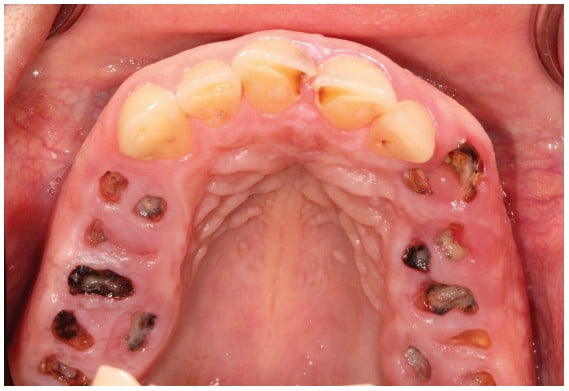

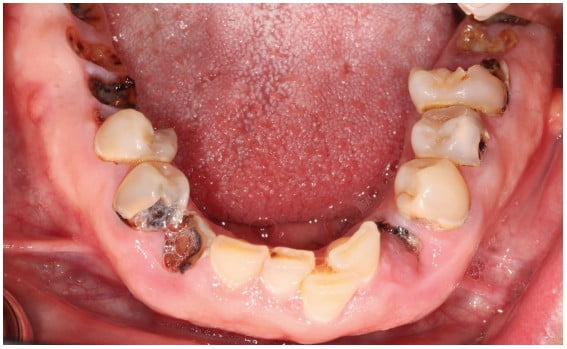

The intraoral exam revealed a significant number of fractured, non-restorable teeth (Figures 3 and 4).

Teeth Nos. 6 to 10 and 23 to 26 were mostly intact. The patient had a Class II Division II anterior malocclusion with a deep overbite. He also had posterior bony hyperplasia and super-eruption of posterior alveolar ridges with no interarch space in the maximum intercuspal position (Figure 5).

Imaging

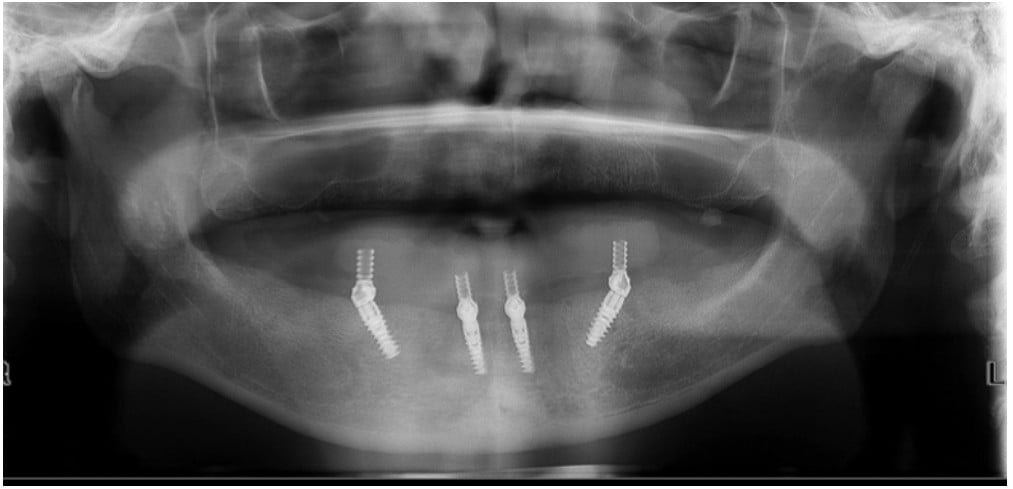

A cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and a panoramic radiograph were obtained (Figure 6). They revealed multiple failing teeth with significant caries and multiple periapical radiolucent lesions around teeth Nos. 2 to 5, 11 to 14, 18, 19, 22, 30, and 31. There was ample mandibular bone for implants after extraction of all teeth and removal of infection. There was a lack of posterior maxillary bone for implants due to sinus pneumatization.

Diagnosis

- Non-restorable maxillary and man-dibular dentition

- Class II malocclusion

- Vertical maxillary excess

- Posterior alveolar hyperplasia

- Unacceptable esthetics

Treatment plan

- Extraction of all teeth and alveoplasty of excessive maxillary bone prior to delivery of a maxillary immediate complete denture

- Extraction of all mandibular teeth and placement of four implants between the mental foramina. In the anterior mandible, implants were planned axially versus tilted posterior implants to avoid the mental foramen and increase the anterior-posterior (A-P) spread

- After healing, fabrication of a cobalt-chrome reinforced maxillary complete denture and a CAD/CAM titanium/acrylic-fixed hybrid prosthesis

- Follow-up with the patient every 6 months

Prosthetic phase

After the review of the CBCT, adequate bone existed for mandibular implants after the creation of adequate prosthetic space by a pre-implant alveoplasty for a hybrid prosthesis. Impressions were made, and casts were articulated accordingly. Teeth were arranged in a Class I relationship (Figure 7).

A maxillary immediate complete denture was fabricated. Heat-polymerized acrylic resin was used to fabricate a mandibular removable prosthesis that would be modified into a fixed provisional prosthesis. Both prostheses were duplicated in clear acrylic resin that served as the surgical template.

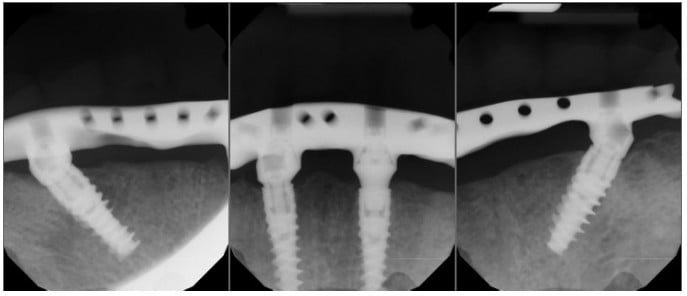

Surgical phase

The patient was given a preoperative benzodiazepine to decrease anxiety prior to surgery, followed by intravenous sedation administered by a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) with appropriate monitoring (EKG lead, pulse oximeter, blood pressure cuff, and carbon dioxide monitoring). Profound local anesthesia was achieved, all teeth were extracted, and bone was reduced according to the surgical templates. Four 13 mm long Nobel Biocare™ (NobelActive®) implants were placed in the mandible with a primary torque of 50 Ncm. Straight abutments were placed on the anterior implants, and 30-degree multi-unit abutments (MUAs) were placed on the tilted implants. White healing caps were placed, and continuous sutures helped obtain primary closure and ensure adequate hemostasis. Postoperative periapical radiographs were taken prior to the prosthodontics phase of treatment (Figure 8).

Prosthodontic phase

High primary torque of the implants allowed for immediate prosthetic loading. A vinyl polysiloxane (VPS) putty material was used to make an abutment-level impression. Anterior abutment positions were indexed in the provisional prosthesis, and holes were drilled in the No. 23 and No. 26 positions. After attaching temporary copings in the No. 23 and No. 26 positions, auto-polymerizing acrylic resin was syringed to secure the copings to the prosthesis. Rigidity of the components in the prosthesis was verified before sending it to the dental laboratory for processing into a fixed-detachable prosthesis. The prosthesis was delivered, and periapical radiographs were taken to verify seating prior to occlusal adjustment.

Definitive prostheses

Healing was uneventful, and 4 months later a panoramic radiograph was taken (Figure 9). The patient was asked about esthetic or functional changes to the definitive prostheses, and notes were made accordingly.

New definitive impressions were made using custom trays for both prostheses. New master casts were fabricated and articulated on a semi-adjustable articulator. Teeth were rearranged for another wax try-in, verifying esthetics and the maxillomandibular relationship (Figure 10).

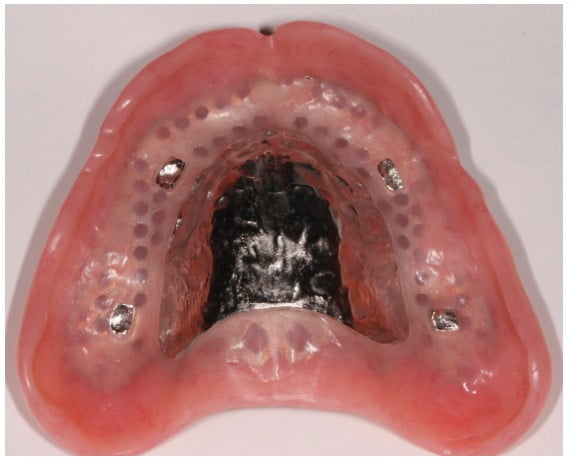

After making appropriate changes to the teeth, the master casts were indexed prior to fabrication of a cobalt-chrome maxillary framework (Figure 11) and a mandibular CAD/CAM titanium framework. Both frameworks were fabricated and tried-in. Periapical radiographs were taken to verify a passive fit of the mandibular fixed hybrid prosthesis (Figure 12).

Both prostheses were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the occlusion was evaluated for centric relation and centric occlusion to be coincident using a bilateral balanced occlusal scheme.

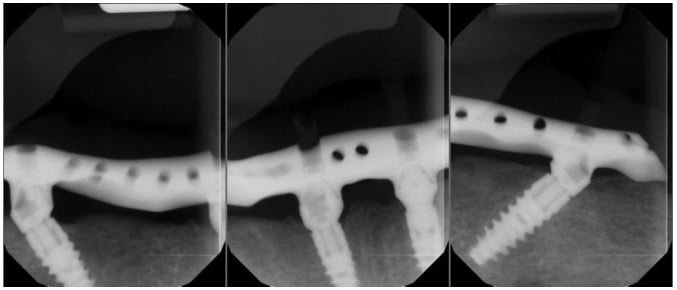

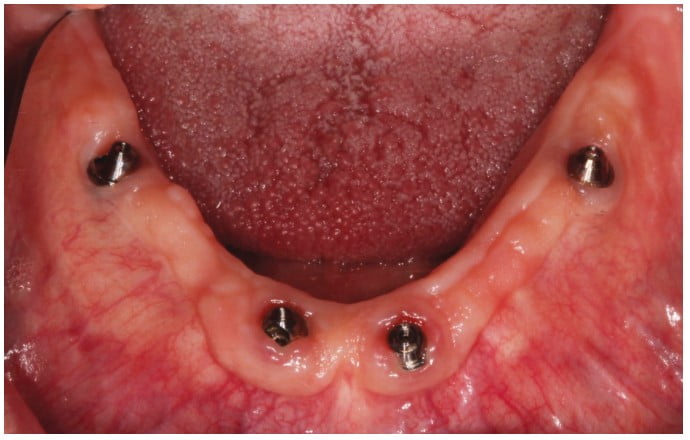

Home care instructions were given, and the use of a water flosser demonstrated. The patient was instructed to maintain good oral hygiene and return to the dentist for regular examinations. He was contacted 1 month later but failed to attend any appointments for 5 years. After 5 years, the patient was concerned a filling had come out from the lower prosthesis. Radiographs taken showed excellent bone levels around the implants (Figure 13), and clinically, the soft tissues were healthy (Figure 14).

Conclusion

It is important to consider the consequences of dental phobia for our patients and how it impacts their daily lives. Patients do not wish to live with physical pain or isolation and must be treated with understanding. This case demonstrates the management of such a patient using sedation for surgery and an implant-supported hybrid prosthesis.

Dr. Justin Moody calmed his own “dental anxiety” when he opened his practice by “going with the workflow.” Read his insights about a systems-driven implant practice: https://implantpracticeus.com/systems-driven-dental-implant-practice/

- Freeman R. Barriers to accessing dental care: Patient factors. Br Dent J. 1999;187(3): 141-144.

- Nuttall N. Review of attendance behavior. Dent Update.1997; 24(3):111–114.

- Vassend O. Anxiety, pain and discomfort associated with dental treatment. Behav Res Ther.1993; 31(7):659–666.

- Armfield JM. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: A review. Aust Dent J. 2013; 58(4):390–407.

- Berg M. Dental fear in children: clinical consequences. Suggested behavior management strategies in treating children with dental fear. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9 (Suppl 1):41–46.

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores