Dr. Istvan Urban explains the processes and concepts behind his innovative — and less invasive — approach to bone regeneration

You are widely known for developing the “sausage technique.” Can you explain a little of the theory behind this procedure?

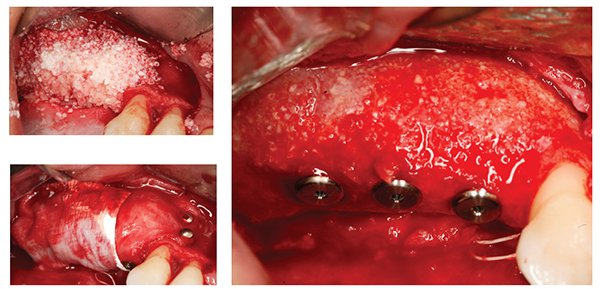

Prior to the sausage technique, we had to utilize more autogenous bone blocks, which is a pretty invasive procedure. The sausage technique is minimally invasive compared to this, which is one of the biggest advantages. Now, we can utilize particulate bone graft composed of 50% of autogenous bone scrapings and a xenogeneic bone graft. So by mixing these two together, we need to harvest much less autogenous bone.

One big advantage is that the xeno-geneic bone graft maintains the volume of the regenerated crest, whereas the autogenous blocks tended to resorb over time, often meaning you had to repeat the procedure. We have more than 10 years of experience with this technique, which shows it is very stable. Why is it called the sausage technique? Well, simply put, it’s because we use a native collagen membrane, which we stretch out with mini-tacks to completely immobilize the bone graft. Using the membrane in this way, like a skin, looks like a little sausage and achieves a very stable bone graft. This membrane beautifully allows the blood vessels to permeate through from the periosteum and the host bone and will resorb in around 4 to 6 weeks. The term sausage technique is not a medical term; rather, it is a technical term to highlight to the clinician that immobilizing the bone graft with the collagen membrane is central to the technique.

How important are the properties of the materials that you use for this technique?

They are very important. Let’s talk about the bone graft — Bio-Oss® (Geistlich) is the most well-studied graft material on the planet. It is very successful because it has the structure of native human bone, which allows for connection between the graft and the host bone.

The other important property is that it is dimensionally stable — it does not resorb too quickly. Allograft, for example, has poor dimensional stability, so we cannot use it for this technique.

The membrane again is native and, again, is very well studied. We know from the research that capillaries from the periosteum can pass through the membrane, which allows for nutrient transfer and vascularization, but at the same time, it does not allow for the ingrowth of soft tissue cells. So it excludes what needs to be excluded and allows what is required for good bone formation.

You have developed a technique that uses a strip of autogenous tissue harvested from the palate, which sits alongside a strip of 3D collagen matrix to gain keratinized tissue. How does this work?

We know that keratinized tissue (KT) is really important around implants, but developing it can be quite an invasive procedure. You have to harvest large quantities of soft tissue from the patient’s palate using a free gingival graft (FGG), which is painful for the patient, and often the outcome can be esthetically poor.

I consider this new approach to be a little bit like tissue engineering: What we are doing is utilizing a collagen matrix, which is designed to stabilize the blood clot of the periosteal bed and allow the soft tissue cells of the neighboring tissues to migrate and to form within the matrix.

If we just use the collagen matrix, we can get some KT, but sometimes we need more than 2 mm-3 mm — after bone grafting, for example, we might need 5 mm or more KT because the mucogingival line has been distorted. In these cases, we can harvest a very thin FGG, which is a source of cells, and position it apically to the collagen matrix — providing cell ingrowth into the collagen matrix.

A big advantage of this technique is that harvesting this thin strip of autograft causes only a negligible amount of pain — something that was observed in our study.

Out of 20 patients involved in the study, 19 didn’t recognize the wound from the mini-strip graft that was harvested from the palate, which is a very big improvement compared to the FGG, or connective tissue graft.

The other thing we see is that since the matrix is collecting cells from palate and cells from the strip of autograft, it is more esthetically pleasing than the FGG. So we have less morbidity, less potential for bleeding, better-looking soft tissue, and very good attached KT. Now, in a new study — to be published soon — we can demonstrate using histology that we are really developing KT with this technique.

You have recently become a board member at the Osteology Foundation. Can you tell us a little bit about your role?

For me, it is an honor to be a board member of the Osteology Foundation. I think it’s a great foundation, and the work on the communication committee is really exciting.

The foundation already communicates well with dentists, and I think most dental practitioners know and like the major symposiums. But there is still room to develop and reach out to dental communities and communicate, not only through the symposiums, but also throughout the year.

For example, if you have a group of dentists running a study club, the Osteology Foundation can support them with speakers, by helping to develop research protocols and ensuring they have a platform where they can communicate with each other, with the Osteology Foundation and with other study clubs.

To have a platform where we could standardize documentation and make it easier to evaluate cases would be a big step and would help to promote education, science, and communication between dentists.

Can you tell me a little more about your involvement with this organization and your lecture at the symposium in April?

I am lecturing on vertical ridge augmentation at the International Osteology Symposium 2016 in Monaco. The vertical defect is probably the most advanced defect, but is probably a little over-mystified, and I think it can be treated by most specialists.

I will talk about the biology of this defect, the biomaterials that should be utilized — what we use and get good results with. I will also talk about the completely resorbed maxilla and utilizing GBR to regenerate in a vertical and horizontal direction — which is very exciting because we are just publishing a study that shows 15 years of follow-up with this indication, which was not an indication before GBR.

So I am really looking forward to April, as it is one of my favorite congresses.

Finally, can you tell us a little bit about your institute in Budapest and your courses?

We have a regeneration institute, which I think is the only institute in the world dealing specifically with bone and soft tissue regeneration. The most popular course is a 3-day course on advanced bone and soft tissue regeneration where we teach the sausage technique, vertical ridge augmentation, and also techniques for comprehensive soft tissue reconstruction of these defects. The course includes live surgery and hands-on with cadavers. We now also have the “Regenerator Program,” which is over three sessions and covers everything in regeneration from the extraction socket and single tooth defect to the vertical ridge defect and comes with a university certification.

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Istvan Urban, DMD, MD, PhD (Budapest), is assistant professor at the implant dentistry program at Loma Linda University, California. He also has a private practice in Budapest, Hungary.

Istvan Urban, DMD, MD, PhD (Budapest), is assistant professor at the implant dentistry program at Loma Linda University, California. He also has a private practice in Budapest, Hungary.