Dr. Steven Vorholt looks at a complicated postoperative complication and offers insight into how to address the challenges to facilitate a successful implant procedure.

Dr. Steven Vorholt illustrates management of a common implant surgery postoperative complication

Incision line opening is the most common postoperative complication that implant surgeons must handle. Being comfortable with the etiology, outcomes, and treatment is key for any implant surgeon whether he/she is beginning the implant journey or is very experienced. In this article, I will showcase several examples of incision line opening seen at routine follow-up appointments, and how they are treated based on their presentation and patient history (Figures 1-5).

Incision line opening can have a multitude of causes. Increased risk has been noted in patients with smoking habits, diabetes, alcohol use, and obesity. Increased likelihood of incision line opening also can stem from iatrogenic causes such as poor incision design, poor suturing technique, lack of tension-free closure, and overextended temporary prosthetics. Use of pre- and postoperative chlorhexidine 0.12% rinse and an oral antibiotic loading dose have shown less likelihood of postoperative acute infections and more predictable healing.

The rule of thumb in most incision line opening cases is to wait and perform no treatment, inspect the area for secondary intention healing, relieve any temporary prosthetic, prescribe chlorhexidine rinse, and re-evaluate weekly as the wound continues to heal and close. Generally, you can expect some thinner tissue over the crest where the incision had opened and some minor early crestal bone loss around the affected implants.

Attempting to resuture at 1-2 weeks postoperatively is extremely difficult as the healing tissue edges are very friable and easily torn. Resuturing is most appropriate very shortly after surgery (1-2 days) or if the wound edges have fully healed but have not closed (2-3 weeks) (Figures 6-9). In the latter case, the wound edges have fully healed with keratinized tissue and are unlikely to close further. The wound edges must be freshened to expose the connective tissue, often with a coarse diamond bur or fresh scalpel, and resutured with tension-free closure. This can be accomplished with primary closure, if possible, or with secondary intention healing and close follow-up.

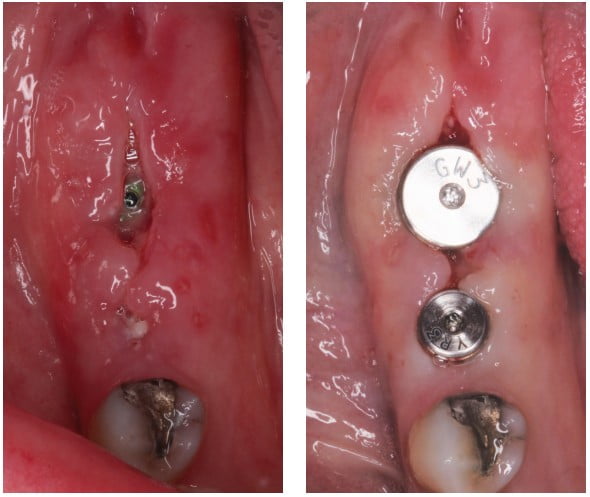

The major concern of incision line opening is early implant exposure. Exposure of the cover screw to the oral environment can lead to early crestal bone loss, infection, and even loss of the implant. When the incision opens, but there is fresh new tissue granulating over the implant sites, no treatment is necessary. Gentle chlorhexidine rinses twice a day and a weekly re-evaluation are adequate. The tissue that heals over these areas is typically thinner than the patient’s biotype, and some minor crestal bone loss may be expected; but typically, it otherwise heals without issue. When a cover screw is partially or fully exposed to the oral environment, a decision must be made on how to treat the area. Surgical notes should be reviewed to confirm the primary stability and insertion torque from the day of surgery. If within 2 weeks and if the insertion torque was adequate (> 32Ncm is a well-established benchmark), exchanging the cover screw for a low-profile healing abutment is suggested. This allows the new granulating tissue to heal around the healing abutment and not have to close over a titanium cover screw, something that is unlikely to happen naturally.

Relieving any temporary prosthetic and patient home-care instructions to avoid the area is critical. Alternatively, the ISQ of the implant can be ascertained with an resonance frequency analysis (RFA) device like the Osstell® (Figures 12-15). An ISQ above 65 is a general benchmark to place a healing abutment.

This brings to light the importance of good primary stability in implant surgery even when not attempting single-stage surgeries. The ability to exchange for a healing abutment at a 10-day follow-up when needed can save the surgeon and the patient time, money, and a guarded prognosis for the crestal bone health of the implant. When both torque and ISQ are inadequate for healing abutment placement, the wound should be monitored until the edges are healed or near closing when the wound edges can be freshened, and resuturing attempted with a membrane to help facilitate closure. A cytoplast PTFE membrane can be helpful to allow tissue coverage in situations like this. Alternatively, the clinician can turn to other adjunctive techniques to help soft tissue healing.

One important adjunctive tool that has become more and more influential in dental surgery has been the incorporation of platelet rich fibrin (PRF). PRF has been shown to increase soft tissue healing of wounds by placing dense concentrates of progenitor cells and clotting and tissue factors directly to the site (Figures 16-18). Empirically, I have seen much more predictable healing and speedy soft tissue healing when PRF is utilized. PRF can also be used to help treat incision line openings. Blood is drawn from the patient and spun using the PRF protocol and used to help pack the wound with PRF membranes. With the healing potential of the site increased, often I see impressive early healing or faster secondary intention healing.

Combining these techniques is sometimes necessary with more aggressive incision line openings. In severe cases of wound dehiscence, we relieve (or suggest not wearing altogether) the removable prosthesis, exchange cover screws for healing abutments, and utilize blood concentrates for increased soft tissue healing.

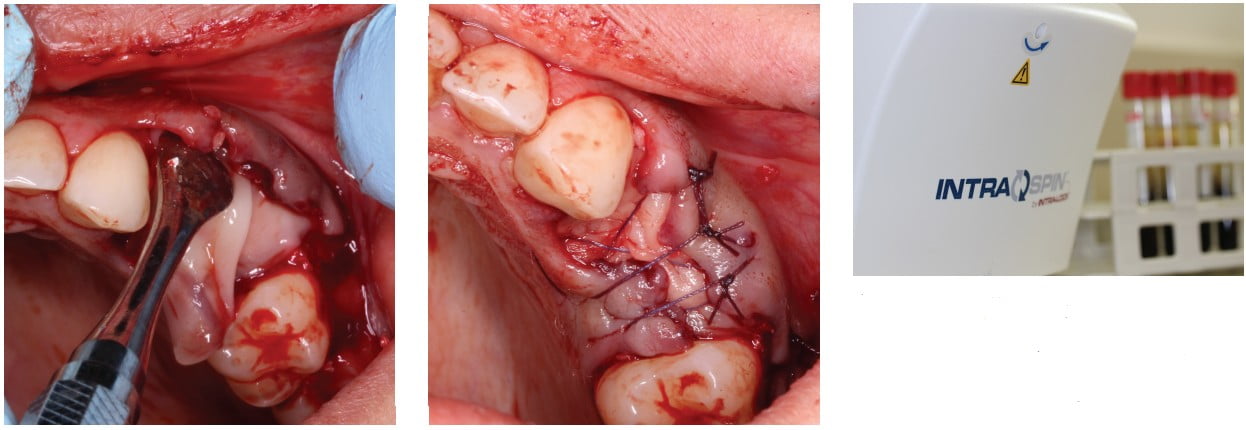

For this patient, we had to use all our techniques to encourage healing of a severe chronic open incision line. At no point in this process was the patient in any amount of discomfort or pain, but the intraoral presentation was genuinely concerning to the patient. The surgery included placement of six implants in between the mental foramen after alveoloplasty in an already edentulous mandible (Figure 19). Primary closure was obtained the day of surgery, but patient returned at 2 days for “loose stitches” (Figure 20). The next 6 weeks involved numerous attempts and techniques to close the incision line. The four exposed implants were exchanged for healing abutments, and the patient was instructed not to wear a lower prosthesis (Figure 21). When the patient presented 2 days postoperatively, I attempted to restore after using a scalpel blade to attempt bilayer closure (Figures 22 and 23). Chlorhexidine rinses were prescribed twice daily for gentle rinse.

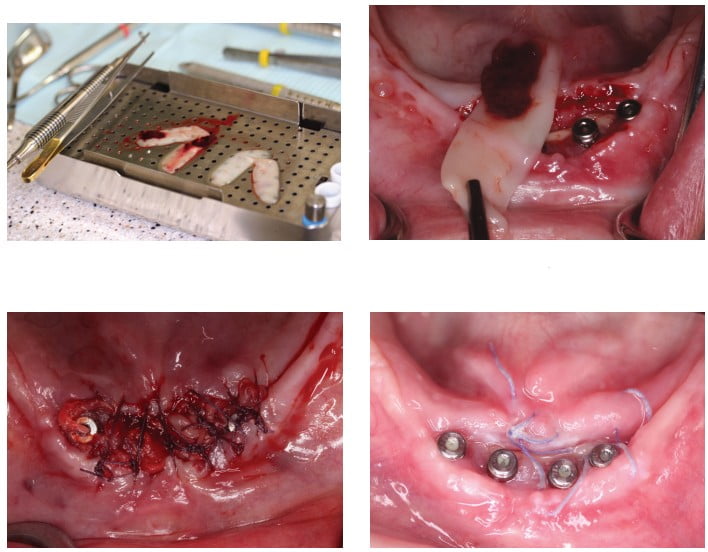

The patient returned 2 weeks later with minimal tissue closure and some exposed bone. At this point, the edge of the incision had fully healed and was covered in keratinized tissue (Figure 24). The decision was made to freshen the edges of the flap with a coarse diamond to initiate fresh bleeding and secondary wound closure (Figures 25 and 26). At the same appointment, the patient’s blood was drawn to make L-PRF membranes that were tucked into the margins of the incision line (Figure 27 and 28). The L-PRF membranes were loosely sutured in between the healing abutments and wound edges (Figure 29).

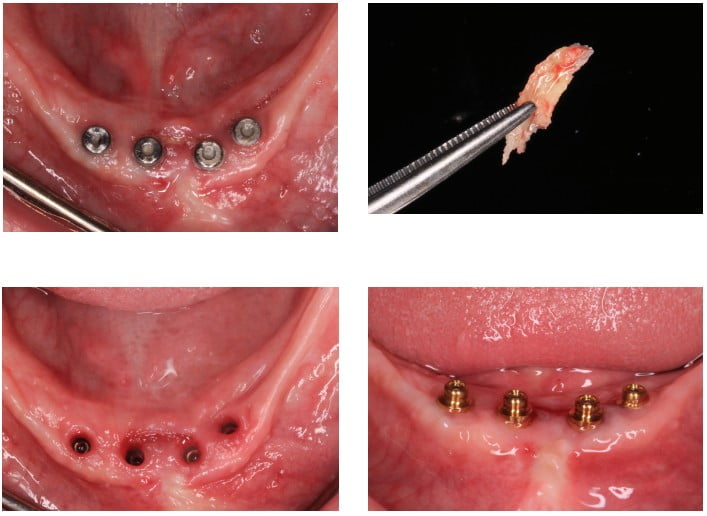

The patient returned one week later with significant new soft tissue coverage of the exposed bone and fresh granulating tissue over the wound (Figure 30). The patient returned 6 months later and exhibited full soft tissue fill (Figure 31). A fragment of necrotic bone was noted between the two middle implants and removed with cotton pliers with no anesthesia (Figure 32). Final soft tissue healing around the implant platforms is seen (Figure 33) prior to selection of final overdenture abutments (OD Secure, BioHorizons) (Figure 34).

Takeaways

Managing the most common implant surgery postoperative complication is an important skill set for every implant surgeon. Understanding that most of the time the treatment necessary is to do nothing but observe, reassure the patient, and allow the body to heal is the first step. Knowing when and how to intervene is also vital. Allowing early implant exposure to go untreated can lead to more crestal bone loss, unesthetic restorations, or poorer long-term prognosis for the dental implants. Using the information from the date of surgery and/or the use of ISQ via RFA tools can help provide early intervention to avoid longer-term complications. Bringing PRF into your practice at the day of surgery or as an adjunct to help wound dehiscence treatment can be a great tool to have in your back pocket as well.

Read about how Dr. Vorholt learned from his first postoperative complication implant failure in “What are you going to do now?” here:

https://implantpracticeus.com/industry-news/what-are-you-going-to-do-now/

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores