Drs. Andrew Shelley and Richard Oliver examine how to prepare for the risk of hemorrhage when placing implants in the lower jaw

While tooth loss in industrialized countries is in decline, the population is rising at the same time — and with it, the proportion of people over the age of 65. This means that there will remain a significant number of edentulous individuals in the population. Many edentulous patients struggle to function, leading to a decline in their quality of life (Thomason, et al., 2009).

This is particularly true of lower complete dentures where looseness and discomfort are common.

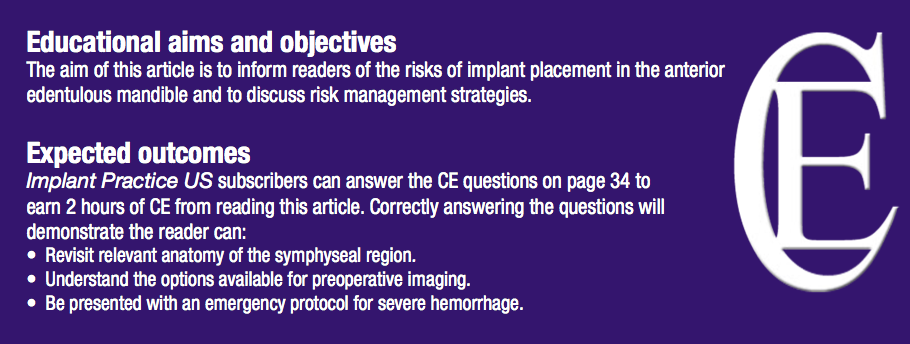

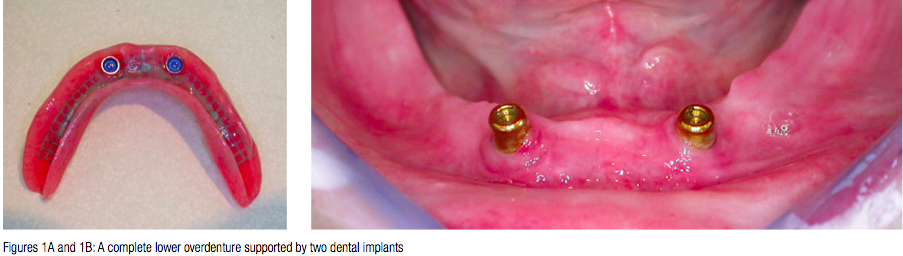

The placement of two dental implants in the anterior mandible allows methods of additional retention to be used to support complete lower dentures (Figure 1). In the York and in the McGill consensus documents, implant-supported overdentures are regarded as the first choice of treatment for the edentulous mandible (Thomason, et al., 2009; Feine, et al., 2002). Nevertheless, the placement of dental implants in the edentulous anterior mandible is not without its risks (Figure 2).

On the lingual surface of the anterior mandible is an anastomosis of vessels arising from both the sublingual artery — which is a branch of the lingual artery — and the submental artery, which is a branch of the facial artery. In addition there are perforating branches through the mandible from branches of the inferior alveolar artery. There is, therefore, a rich plexus of arteries just lingual to where we wish to place our osteotomies when placing implants to support a complete lower overdenture.

On the lingual surface of the anterior mandible is an anastomosis of vessels arising from both the sublingual artery — which is a branch of the lingual artery — and the submental artery, which is a branch of the facial artery. In addition there are perforating branches through the mandible from branches of the inferior alveolar artery. There is, therefore, a rich plexus of arteries just lingual to where we wish to place our osteotomies when placing implants to support a complete lower overdenture.

Alveolar resorption can leave the anterior mandible very shallow, narrow, or knife-edged, and there is often a natural lingual concavity. Therefore, there is a significant risk of perforation through the lingual surface. The consequences of perforation and trauma to these vessels may be dramatic and serious since a severe hemorrhage spreading from the sublingual space can cause elevation of the tongue and threaten the airway. One such case was reported in the UK in 2009 (Pigadas, et al.), but a search of the literature reveals that at least 20 other cases have been reported. Some of these cases are reported as “potentially fatal” or even “near fatal.”

Many of the patients in these reports were fortunate enough to be in a situation where an emergency tracheotomy could be performed to save the patient’s life. Nevertheless, there are also anecdotal reports of fatalities. We cannot know how many cases remain unreported.

Preventing hemorrhage

Naturally, implant dentists will seek to prevent this occurrence and protect their patients from a potentially life threatening situation. So what can be done?

Anatomy

It is, of course, important to be aware of the form of the mandible in advance. There are several sources of information. First, preoperative palpation of the area will give some indication of the size and shape of the mandible, although this is limited. At the time of surgery, it is possible to raise a periosteal flap and explore the form of the anterior mandible with, for example, a periosteal elevator. Nevertheless, in itself, this risks damage to arteries on the lingual surface. Perforating arteries can enter the symphyseal bone through lingual foramina. Such foramina are most often at the midline but can be more widely distributed. The diameter of the sublingual artery at this point has been reported to be up to 1.8 mm in diameter, and anastomoses may cause a copious blood flow if damage occurs. Such exploration of the area should therefore be conducted with caution, avoiding the midline if possible.

A cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) image of an edentulous mandible at the midline clearly demonstrates significant foramina, which carry perforating arterial branches (Figure 3). Some clinicians may place a metal retractor against the lingual bone to protect the soft tissues against accidental perforation of the lingual plate when preparing an osteotomy. If this is done, retraction should be no deeper than necessary to protect the soft tissues and should avoid the midline where perforating branches are common.

Imaging

Radiography plays an important part in the preoperative assessment of the form of the anterior edentulous mandible, and a number of views are available.

A panoramic radiograph will give a two-dimensional view of the mandible but little information about the crucial cross-sectional form. Use of ball bearings at the potential implant sites will give useful planning information and a reference diameter from which to take measurements (Figure 4). A panoramic view can be supplemented with a lateral cephalometric image, which will give a superimposition of the anterior mandible in cross-section. Nevertheless, a convenient alternative in the practice situation is the transymphyseal view, in which a periapical radiograph is used extraorally to give a similar image to the lateral cephalogram at a lower effective dose (Shelley and Horner, 2008). This is illustrated in Figure 5.

Three-dimensional views such as conventional and computed tomography are available, although in dentistry, the availability of CBCT has largely replaced other three-dimensional views. CBCT machines are now becoming commonly available in practices and specialist imaging centers. CBCT views will give a true cross-sectional image at exactly the site of the proposed dental implant. Nevertheless, there are reasons not to take CBCT images just as there are reasons to take them.

Individual machines vary, but while the effective radiation dose to the patient is something like one-tenth of that of medical CT, it is still around 10 times that of a panoramic view, and we have a professional duty to keep radiation dose as low as reasonably practical. Furthermore, while it may seem like a reasonable assumption, there is presently no evidence to support the suggestion that the availability of three-dimensional images is helpful in preventing damage to the lingual vessels (Shelley, at al., 2013).

Therefore, research does not presently exist to help us choose the most appropriate balance between effective dose to the patient and availability of comprehensive images. You might expect dentists to be in broad agreement as to which views are appropriate for the preoperative imaging of the anterior edentulous mandible prior to dental implant placement. This is not the case. A recent survey of UK dentists revealed a chaotic pattern of prescription of views for this situation (Shelley, et al., 2013).

Most dentists began with either a panoramic view or a CBCT view. From the results of this first view, some dentists prescribed supplementary views and some did not. The prescription pattern was similar for both a difficult and a relatively easy case. Surprisingly, a small number of dentists prescribed no radiographs at all. One reason for confusion might be that existing guidelines are conflicting. For example, the latest guidelines of the European Association of Osseointegration (EAO) were issued in 2012 and state: “If the clinical assessment of implant sites indicates that there is sufficient bone width, and the conventional radiographic examination reveals the relevant anatomical boundaries and adequate bone height and space, no additional imaging is required for implant placement.”

Conversely, in the same year the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiologists (AAOMR) issued guidelines that read: “AAOMR recommends that cross-sectional imaging be used for the assessment of all dental implant sites and that CBCT is the imaging method of choice for gaining this information.”

Implant length

Choice of implant length may be important.

In a review of the literature, Kalpidis and Setayesh (2004) report an association between the use of longer implants in the anterior edentulous mandible and the occurrence of dangerous bleeding episodes. At the same time, the use of shorter implants in mandibular bone can be very successful.

In the case of implant placement in the anterior mandible, therefore, it may be sensible to reconsider the concept of bicortical anchorage and use of long implants.

Hemorrhage in practice

So what would it be like if there is trauma to a lingual vessel, and what can be done as an emergency measure? In some cases, the bleeding will be very slow, and a contained swelling may develop over 24 hours. An example is shown in Figure 6. This patient’s airway was not endangered.

So what would it be like if there is trauma to a lingual vessel, and what can be done as an emergency measure? In some cases, the bleeding will be very slow, and a contained swelling may develop over 24 hours. An example is shown in Figure 6. This patient’s airway was not endangered.

On the other hand, bleeding can be rapid and dramatic. In Figure 7, you can see a massive hematoma that is displacing the tongue and endangering the patient’s airway. In the hospital situation, you are likely to be surrounded by the appropriate facilities, equipment, and personnel to avoid the worst happening. But what would you do in practice? It has been suggested that the arteries can be tied off to stem the bleeding. However, few of us would feel confident to do this in an emergency situation, if at all.

Furthermore, a damaged artery will retract and be more difficult to identify. Searching in the floor of the mouth for an artery to tie off in the presence of an actively expanding hematoma is only likely to worsen the situation and precipitate a deeper crisis. Even the most experienced maxillofacial surgeons are likely to regard this as unwise.

In a hospital, it is most likely that the airway will be protected by intubation with a nasotracheal or orotracheal airway. However, as a hemorrhage extends to endanger the patient’s airway, intubation will become more difficult and may become impossible. Does this mean that dentists who place implants in the practice situation should be trained to intubate patients at an early stage? The remaining alternative is an emergency tracheotomy — so should that also form part of training for implant practitioners?

Even the most thorough training in this regard is unlikely to be accompanied by significant practical experience. Therefore, if an implant practitioner were called upon to do this, he or she would be carrying out an unfamiliar procedure, in an emergency situation, for the first time. Further, intubation and emergency tracheotomy, in the hands of the inexperienced, have the potential to turn urgency into crisis. On balance, therefore, the authors of this article believe that it is not appropriate for most dentists to attempt intubation or tracheotomy in the practice situation in other than the most extreme of circumstances.

Emergency protocols

If you encounter a hemorrhage in the floor of the mouth, we believe a sensible protocol for the practice situation is as follows.

First, take immediate action. Do not wait. Take two large gauze pads. Place one in the floor of the mouth at the site of the bleeding and the other extraorally on the other side of the floor of the mouth. Then apply pressure to the floor of the mouth by squeezing the pads together with your fingers and thumb. A mouth prop on the opposite side of the mouth may be helpful to maintain opening. Telephone the emergency services, and explain that you have a patient who has a bleed in the floor of the mouth and that the airway is endangered. Intubation, if it is appropriate, will then be carried out by those with appropriate training and experience.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the risk of a potentially fatal hemorrhage in the floor of the mouth following dental implant placement in the edentulous mandible seems to be under recognized. While it is unlikely that an implant practitioner will encounter this, many cases have been reported in the literature, and the potential certainly exists. The use of implants that are as long as possible in order to establish bicortical anchorage should be discouraged in the edentulous anterior mandible.

Preoperative diagnostic imaging is probably important, but evidence is still emerging to help us choose the appropriate views for different cases, and current guidelines are conflicting. Until such evidence emerges, it seems sensible practice to prescribe CBCT images for challenging cases such as the more atrophic mandibles.

Protection of the lingual soft tissue with a metal retractor, when preparing an osteotomy, may be a sensible precaution, but operators should be aware of the possible presence of perforating arteries, especially near the midline. It is also wise to discuss a simple emergency protocol with the team and ensure that appropriate materials are available. Crucially, when placing implants in the edentulous anterior mandible, a thorough understanding of anatomy and awareness of the potential for a fatal hemorrhagic episode is possibly the best protection.

References

- Feine JS, Carlsson GE, Awad MA, Chehade A, Duncan WJ, Gizani S, Head T, Heydecke G, Lund JP, MacEntee M, Mericske-Stern R, Mojon P, Morais JA, Naert I, Payne AG, Penrod J, Stoker GT, Tawse-Smith A, Taylor TD, Thomason JM, Thomson WM, Wismeijer D. The McGill consensus statement on overdentures. Mandibular two-implant overdentures as first choice standard of care for edentulous patients. Gerodontology. 2002;19(1):3-4.

- Pigadas N, Simoes P,Tuffin JR. Massive sublingual haematoma following osseo-integrated implant placement in the anterior mandible. Br

DentJ. 2009;206(2):67-68. - Shelley A, Horner K. A transymphyseal X-ray projection to assess the anterior edentulous mandible prior to implant placement. DentUpdate. 2008;35(10):689-694.

- Shelley AM, Glenny AM, Goodwin M, Brunton P, Horner K. Conventional radiography and cross-sectional imaging when planning dental implants in the anterior edentulous mandible to support an overdenture: a systematic review. DentomaxillofacRadiol. 2014;43(2).

- Shelley AM, Wardle L, Goodwin M, Brunton P, Horner K. A questionnaire study to investigate custom and practice of imaging methods for the anterior region of the mandible prior to dental implant placement. Dentomaxillofac

Radiol. 2013;42(3). - Thomason JM, Feine J, Exley C, Moynihan P, Müller F, Naert I, Ellis JS, Barclay C, Butterworth C, Scott B, Lynch C, Stewardson D, Smith P, Welfare R, Hyde P, McAndrew R, Fenlon M, Barclay S, Barker D. Mandibular two implant-supported overdentures as the first choice standard of care for edentulous patients – the York Consensus Statement. BrDentJ. 2009;207(4):185-186.

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores