Dr. Bernard Touati offers his insights into effective techniques and procedures for soft tissue management in the anterior region

In the following article, I will do my best to explain the main factors influencing hard and soft tissue remodeling around implants and make suggestions on how to achieve optimal integration in the esthetic zone. Among other aspects of treatment, I will cover diagnostics, treatment planning and risk assessment, ideal 3D bone-level implant placement, the relevance of good hard tissue volume and architecture, as well as the importance of thick and stable soft tissue in the transmucosal zone.

[userloggedin]

When we deal with dental implants in the anterior region, we are looking for more than osseointegration. We — dentists and patients alike — are looking for optimal soft tissue integration. We are looking for the perfect pink score.

In the anterior region, esthetic perfection is not a choice, but an obligation. Patients want their peri-implant soft tissues to mimic the soft tissue around natural teeth. There are, of course, many differences between teeth and implants. When we produce restorations based on natural teeth, the gingiva is only dealing with the margin of the crown. We locate our margin at the gingival or intra-sulcular level, but not transmucosally.

When we deal with implants, on the other hand, we need to take into consideration the mucosal barrier, and the mucosal barrier is quite different on implants than on teeth for a variety of reasons. The problem is that when we want to do something transmucosally — for the abutment or at the neck of the implant — we need the soft tissue to adhere to the prosthetic surface of the implant. This is different than working with natural teeth because it involves many biological factors. To achieve harmonious soft tissue integration, we obviously have to take into account all the biological, functional, and esthetic factors.

When we deal with implants, on the other hand, we need to take into consideration the mucosal barrier, and the mucosal barrier is quite different on implants than on teeth for a variety of reasons. The problem is that when we want to do something transmucosally — for the abutment or at the neck of the implant — we need the soft tissue to adhere to the prosthetic surface of the implant. This is different than working with natural teeth because it involves many biological factors. To achieve harmonious soft tissue integration, we obviously have to take into account all the biological, functional, and esthetic factors.

And not just in two dimensions!

We also have to remember that our work will not be evaluated by the two-dimensional photographic images we use to document the treatment, but in the homes, on the streets, and at the workplaces where our patients go about their day-to-day lives. Thus, we need to achieve three-dimensional integration. We need to have the scalloping, the volume, the papillae, the texture, the color, and the absence of scars that are characteristic of healthy, natural teeth.

We also have to remember that our work will not be evaluated by the two-dimensional photographic images we use to document the treatment, but in the homes, on the streets, and at the workplaces where our patients go about their day-to-day lives. Thus, we need to achieve three-dimensional integration. We need to have the scalloping, the volume, the papillae, the texture, the color, and the absence of scars that are characteristic of healthy, natural teeth.

Five major factors

The main factors that influence tissue remodeling around implants can be organized into five categories: anatomical, surgical, implant, patient, and prosthetic (see Table 1).

Among the anatomical considerations are the tissue biotype, the thickness of the bone plates, the thickness of the soft tissue, and the lack of attached gingiva. I can testify from experience that the tissue biotype and the thickness of the tissue are critical to optimal outcomes.

Among the anatomical considerations are the tissue biotype, the thickness of the bone plates, the thickness of the soft tissue, and the lack of attached gingiva. I can testify from experience that the tissue biotype and the thickness of the tissue are critical to optimal outcomes.

Surgical factors include the three-dimensional positioning of the implant, the choice between a flap or flapless approach, and the kind of soft tissue augmentation that has been carried out. Other factors include bone desiccation, countersinking, bone compression, and (last but not least), the extraction technique used.

Implant design is also important, of course. The design of the neck, the surface properties of the implant, and the type of connection can all be decisive. Questions that become interesting in this context include “Do we have platform shifting available?” Or, “Can the implant be maneuvered during insertion, when necessary, in order to ensure optimal placement?”

We also need to remember that every patient has a specific set of characteristics that influences remodeling. Do they smoke? Do they have good healing potential? Immune factors need to be considered, as well as the patient’s willingness and ability to maintain good oral hygiene.

There are also a great number of prosthetic factors that impact remodeling. The final abutment design, the biomaterial from which they are made, the abutment’s surface properties, connection, and fit are all important factors that contribute to success.

Abutment connections — and disconnections — need to be taken into consideration as well as choices concerning immediate provisionalization and the submergence profile, emergence profile, and the restoration anatomy. We need to be careful about deleterious excess cement (if we have not chosen screw retention, of course) and must take into account good occlusion to prevent excessive load.

Given all these factors — and I have only listed the main ones in the table — I have constructed a roadmap for optimal integration in the esthetic zone.

Diagnose, plan, and assess

To plan for a successful anterior solution, we need to assess risk factors via three-dimensional visual inspection, probing, and employing radiographs. Visually, we can see deformities such as concavities. Probing, we can see where the bone is, and we can also probe at the level of the adjacent teeth to assess the periodontium.

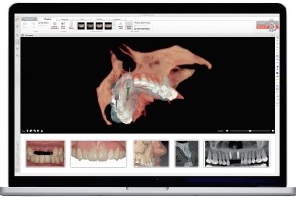

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is an invaluable three-dimensional tool. When connected to software like NobelClinician® (Nobel Biocare®), it provides us with an enormous amount of information that is useful in the decision-making process. It shows us, for example, whether we have a thin buccal plate or a thick one. And this makes a very big difference. The volume and architecture of the site also become clear when using this sort of software.

The thickness of the soft tissue can also be assessed via CBCT. When the patient wears radiographically transparent lip retractors during the imaging process, the resulting CBCT image renders the soft tissue in light gray. Should we then want to harvest some soft tissue from the palate, for example, this technique allows us to objectively measure the tissue available.

It also lets us assess whether the patient has a thick or thin biotype. A delicate biotype will ordinarily require connective tissue grafting, but a thick one generally indicates stable tissue that is forgiving of minor mistakes. When facing thin and moderate soft tissue situations, we need to be more invasive and start considering soft tissue enhancement, grafting procedures, and so on.

Ideal implant placement

The first thing to consider is where the implant is going to be placed. Positioning is critical because even a little deviation can impact the esthetic outcome. The real problem is the transversal plane. We want to insert our implant more toward the palatal, because if we leave too much inclination, we run the risk of reducing the thickness of the buccal plate, which in almost all cases is already very thin. The more an implant allows you to play with its position — in order to put it in solid bone — the better suited it is to situations like these. With a little extra room between the buccal plate and the implant, you will have space to fill in later with bone augmentation material.

Ensuring hard tissue volume and architecture

At this point, we are dealing with where the bone is, and how to make the most of it. Again, we really do need to keep in mind how thin the buccal plate ordinarily is. Natural teeth have Sharpey’s fibers, a blood supply to the periodontium, stimulation, and even though there may not be much (if any) cortical bone on the buccal, the soft tissue still stays in place. With an implant, on the other hand, we run the risk of fenestration through this thin bone if we position implants with the same orientation as natural incisor roots.

The buccal socket wall is predominantly composed of bundle bone (while the lingual one has more lamellar bone). The lack of stimulation and function in the absence of Sharpey’s fibers may explain the remodeling of this buccal wall. The buccal plate often quickly collapses when we extract a tooth — partly because it is thin, and partly because it is mostly composed of bundle bone. Because an implant does not have a periodontium and therefore lacks vascularization, we have a ready explanation as to why we have more remodeling on the buccal side as opposed to the lingual side.

In 60% of anterior cases, buccal bone plates are less than 0.5 mm thick (and we really need 2 mm to get the job done). If we remember these values, we will understand the entire strategy of slightly angulating the implant in the anterior aspect. When building a multiple unit anterior restoration on natural teeth, we still have soft tissue, and the soft tissue is quite stable. But once anterior teeth are extracted, we will almost certainly have to reorient “the root,” inserting the implant palatally.

The good news is that with CBCT — especially when used in conjunction with planning software — the right position can be objectively assessed first, making sure that a gap exists between the implant and the buccal plate. This way we can take steps to thicken the buccal bone plate zone and, thus, provide a safe situation for the future. The key factors for good esthetic results at anterior extraction sites are the integrity of the buccal plate and the thickness of the soft tissue. If those two parameters are promising, implant treatment is more likely to succeed. Of course, in terms of the three-dimensional architecture of the soft tissue and recapturing interdental papillae, the health of the periodontium of the adjoining teeth is important, and probing gives us solid information.

Bone grafting

We can use bone augmentation materials in the “jumping gap” (i.e., the osteogenic “jumping distance,” which is the gap between the implant body and the alveolar wall). In cases with a large defect, guided bone regeneration can be carried out. Adding connective tissue on top of this brings greater thickness to the tissue, which provides greater mechanical resistance and leads to increased blood supply.

In cases where there is no buccal bone post-extraction, a complete socket must first be re-created, which provides a favorable situation for the insertion of an implant and is well within widely-practiced, well-accepted reconstructive protocols.

Establishing thick and stable soft tissue

All of this brings us to the soft tissue. It needs to be thick and stable, especially in the transmucosal zone; stability makes for good esthetics.

Post-extraction remodeling is inevitable. Today, there is no magical way to totally counteract the post-extraction remodeling — it’s biological — but it can be compensated for. One way to compensate for it is to thicken the soft tissue and also to regenerate the bone, when necessary. A connective tissue pouch can be used, both horizontally and vertically. Mucosal enhancement can be realized through connective tissue graft(s).

Not least of all, we can manipulate the soft tissue via subtle changes in the design of the prosthetics.

First, we want to see some concavity transmucosally at the abutment level and/or platform switching in order to thicken the mucosa, creating a virtual “o-ring” of soft tissue. On the other hand, proximally, the prosthetic restorations need to display some convexity in order to gently push the tissue and to keep the interdental papillae.

The vertical position of the implant in relation to the mucosa is very important. This makes it possible for us to play with the emergence profile and then shape the marginal mucosa with the emergence bulk. Adding composite material incrementally, we can guide the marginal mucosa very successfully. This careful step-by-step process takes a substantial amount of time, but gives beautiful results.

This article is a condensed version of a lecture given by Dr. Touati at the Nobel Biocare Global Symposium in New York City last June. It originally appeared in Nobel Biocare News (Vol. 16, No. 1, 2014) and appears with permission. Dr. Touati’s full lecture can be found by visiting the website www.for.org/video-insights and searching for “Bernard Touati.”

[/userloggedin]

[userloggedout][/userloggedout]

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores