Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to discuss the bacteria involved in peri-implantitis and the management of the disease.

Expected outcomes

Implant Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

Take the quiz by clicking here.

- Demonstrate an understanding of the microbiology of peri-implantitis and chronic periodontitis.

- Realize the difference in some microbe detection techniques.

- Identify some complex organisms commonly detected in peri-implantitis.

- Recognize growing evidence that peri-implantitis has its own, unique microbial signature that is distinct to chronic periodontitis

- Recognize the need for management of peri-implantitis, which may entail implementing certain testing protocols from which a suitable antimicrobial can be carefully selected.

Dr. Aneel Jabbar delves into the microbiology of peri-implantitis and how it is distinguished from chronic periodontitis.

Dr. Aneel Jabbar explores whether the microbiology of peri-implantitis is similar to or distinct from chronic periodontitis

Dental implants have become an increasingly favored treatment modality over the past few decades, with rapid evolution of dental implant designs, surgical protocols, and bone grafting techniques. As clinicians, we find that not only are many patients having dental implants placed, but there are also many patients with existing dental implants that require maintenance.

Implant challenges

One of the challenges in implant dentistry today is the management of peri-implantitis, a bacterial-driven inflammatory disease that results in progressive bone loss around dental implants. It is the main long-term biological complication associated with treatment, with Mombelli, et al., (2012), suggesting a 20% prevalence in individuals at 5 to 10 years following placement.

One of the challenges in implant dentistry today is the management of peri-implantitis, a bacterial-driven inflammatory disease that results in progressive bone loss around dental implants. It is the main long-term biological complication associated with treatment, with Mombelli, et al., (2012), suggesting a 20% prevalence in individuals at 5 to 10 years following placement.

A recent literature review by this author investigated the bacteria involved in peri-implantitis. A holistic appreciation of the surgical, prosthetic, and biological risk factors is required in the diagnosis and management of peri-implantitis. Therefore, understanding the microbiology of the failing site is merely one small part of a multifactorial and multifaceted disease process.

Given that clinicians may utilize topical or systemic antimicrobials in addition to surgical intervention as part of their treatment protocol, it is essential that such antimicrobials are selected based on knowledge of the microbes they are targeting.

Given that clinicians may utilize topical or systemic antimicrobials in addition to surgical intervention as part of their treatment protocol, it is essential that such antimicrobials are selected based on knowledge of the microbes they are targeting.

Periodontitis and peri-implantitis have historically been seen as analogous: the difference simply being the subject of the disease — tooth or dental implant. This is partly true, but not entirely. While the clinical parameters that both present with can be similar, there are differences reported in the host response, the rate, and pattern of bone loss.

Historically, the microbes involved in peri-implantitis were believed to be the same as those involved in chronic periodontitis. Recent studies, however, have suggested that the answer may be slightly more nuanced than this.

Literature review

A literature search was conducted involving MEDLINE®/PubMed® and Web of Science databases to gather clinical studies that investigated the microbiology of peri-implantitis, using appropriate search terms and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter the results. The selected studies were reviewed and quality assessed using published guidelines on the analysis of observational studies (Strobe). A total of 25 clinical studies between 1987 and 2015, involving 1,392 participants, were obtained.

With advancements in technology, microbe detection techniques have evolved to yield more information about the microbial profile of a plaque sample, and this is reflected in the diverse number of techniques used in the studies obtained (Table 1). The results obtained in the studies depended heavily on the technique used, with newer molecular techniques (such as 16S pyrosequencing) being well-equipped to detect most, if not all, bacterial species in a sample. In comparison, older techniques — such as DNA-DNA hybridization or bacterial culture and microscopy — were far more limited in their scope.

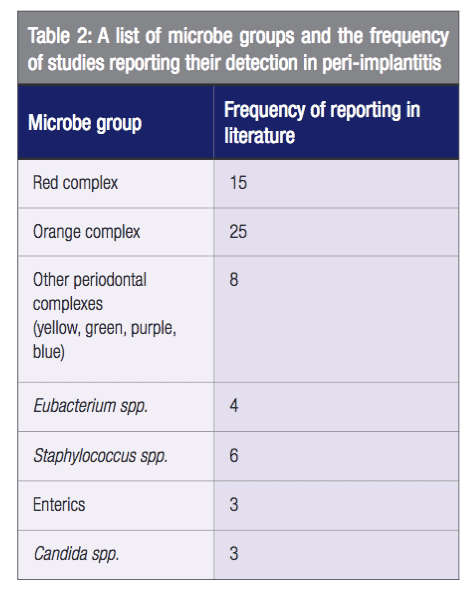

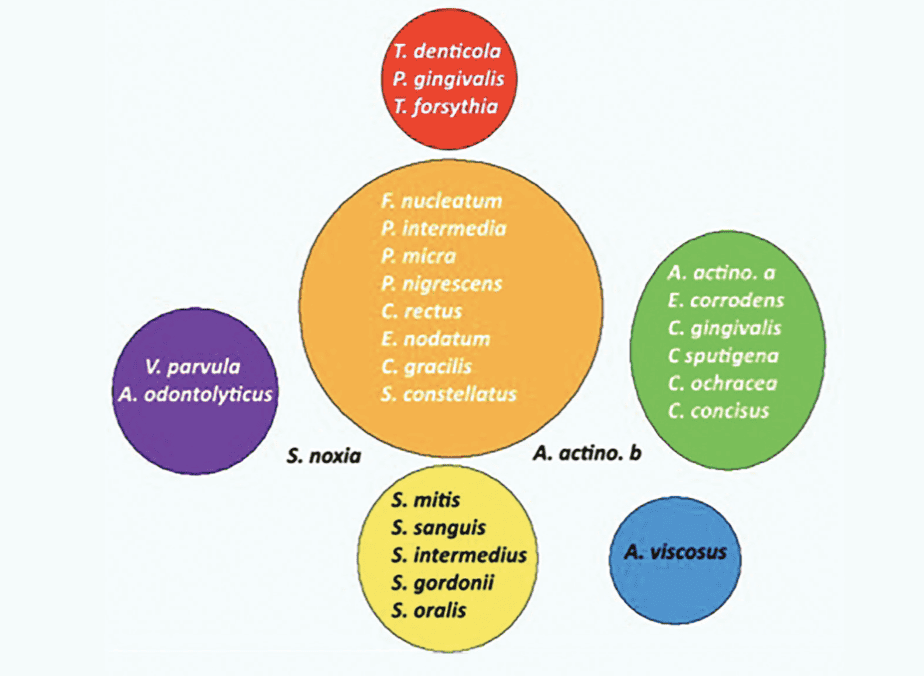

Socransky, et al., (1998), described pathogens associated with chronic periodontitis as working together symbiotically in specific groups, or complexes (Figure 1). Red and orange complex organisms — strongly and moderately linked to bleeding on probing and bone loss in chronic periodontitis, respectively — were commonly detected in peri-implantitis in this review (Table 2).

In addition to this, a number of studies detected non-periodontal opportunistic pathogens at the failing dental implant site, such as Staphylococcus spp., Candida spp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

When assessing the studies that compared chronic periodontitis and peri-implantitis in a split mouth design and used the most current microbe detection technique (16S pyrosequencing), the majority of studies found a significant difference in the overall microbial profiles of the two pathologies.

These findings suggest that the red and orange complex microbes linked to chronic periodontitis are also strongly linked to peri-implantitis. Yet, simultaneously, there is growing evidence that peri-implantitis has its own, unique microbial signature that is distinct to chronic periodontitis. The role of non-periodontal opportunistic species (such as Staphylococcus spp.), and whether or not they play a part in the acute pathological process, is not entirely clear.

Implications on management

In the words of one author, the microbiology of peri-implantitis and chronic periodontitis should be viewed as “fraternal” instead of identical (Robitaille, et al., 2015). In clinical practice, it seems apparent that if we view peri-implantitis as somewhat distinct to chronic periodontitis in terms of its microbiology, then it may encourage us to reflect more on the types of antimicrobials we prescribe — should we choose to use them.

As a crude example, P. aeruginosa, which some studies detected in peri-implantitis, is known to be resistant to chlorhexidine, amoxicillin, and metronidazole, the agents most commonly prescribed for dental infections.

Future management of peri-implantitis may involve obtaining a swab from the peri-implant pocket to send for molecular analysis, on which basis a suitable anti-microbial can be carefully selected. This will help to ensure that antimicrobial therapies are effective in complementing surgical intervention.

The complicated nature of the microbiology of peri-implantitis continues to challenge implantologists. See Dr. Michael Norton’s view of this condition in his article “Understanding peri-implant diseases” here.

References

- Mombelli A, Müller N, Cionca N. The epidemiology of peri-implantitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(Suppl 6): 67-76.

- Robitaille N, Reed DN, Walters JD, Kumar PS. Periodontal and peri-implant diseases: identical or fraternal infections? Mol Oral Microbiol. 2016;31(4):285-301.

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(2):134-44

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Aneel Jabbar BDS, MJDF RCS (Eng), MSc qualified from the University of Bristol in 2010. In 2012, he joined the Royal College of Surgeons with the MJDF postgraduate qualification. He gained a master’s degree in dental implantology from the University of Bristol. He has also received a number of prizes in the field of dental implants, most recently having won the 2017 Congress Poster Prize at the Association of Dental Implantology (ADI) Members’ National Forum. Dr. Jabbar enjoys providing all aspects of dentistry for his patients and has a special interest in dental implants. He is a member of the Association of Dental Implantology and the International Team for Implantology.

Aneel Jabbar BDS, MJDF RCS (Eng), MSc qualified from the University of Bristol in 2010. In 2012, he joined the Royal College of Surgeons with the MJDF postgraduate qualification. He gained a master’s degree in dental implantology from the University of Bristol. He has also received a number of prizes in the field of dental implants, most recently having won the 2017 Congress Poster Prize at the Association of Dental Implantology (ADI) Members’ National Forum. Dr. Jabbar enjoys providing all aspects of dentistry for his patients and has a special interest in dental implants. He is a member of the Association of Dental Implantology and the International Team for Implantology.