Dr. Sam Mohamed uncovers the processes behind an alternative method for increasing horizontal width in cases of alveolar bone resorption

Dr. Sam Mohamed uncovers the processes behind an alternative method for increasing horizontal width in cases of alveolar bone resorption

The surgical placement of dental implants is governed primarily by the nature and design of the final restoration and, secondarily, by the morphology and quality of the alveolar bone. Resorption of the alveolar bone may make implant placement difficult, if it is possible at all.

Following extraction, if no socket preservation is carried out, the alveolar bone undergoes progressive resorption, resulting in reduced width and height. Around 50% of bone width and height is lost in the 6- to 12-month period following extraction. As a consequence, restoratively driven dental implant positioning often entails augmentation of the alveolar ridge and adjacent structures.

There are various surgical techniques to augment alveolar ridges with reduced width, but these carry a risk of increased morbidity and can also result in increased expense and longer treatment times — all of which are factors that can affect the acceptance of treatment by some patients.

There are various surgical techniques to augment alveolar ridges with reduced width, but these carry a risk of increased morbidity and can also result in increased expense and longer treatment times — all of which are factors that can affect the acceptance of treatment by some patients.

Techniques for the management of resorbed alveolar ridges include the following:

- Onlay grafting

- Segmental osteotomy

- Vertical distraction

- Sinus floor augmentation

- Major reconstruction

- Ridge-splitting or bone expansion

These techniques present a number of surgical and prosthetic challenges:

- Inadequate tissue to cover the grafted area.

- Incorrect emergence profile in the presence of undercuts.

- Autogenous bone requires an additional surgical site.

- Small diameter implants could be used: However, if less than 1.5 mm of bone surrounds the implant, the risk of bone loss is greater; therefore, in areas where there is height deficiency, width becomes a more critical factor.

Horizontal augmentation

Alveolar bone splitting and immediate implant placement have been proposed for patients with atrophy of the maxilla in the horizontal dimension. Many lateral augmentation techniques have been successfully adopted for the management of horizontal ridge defects. It is well established that implant placement must be restoratively driven and not bone driven. If one fails to achieve the necessary modifications in bony defects prior to implant placement, then esthetic and/or functional failure is inevitable.Augmentation techniques using autografts or allografts have proven to be successful in highly resorbed ridges, but they have several drawbacks, including invasiveness, the need for an additional donor site, graft resorption, membrane exposure to infection, and delaying of implant placement for grafting maturation. Hence, employing such techniques in moderate horizontal ridge defects (less than 4 mm) is not necessary.

Alveolar bone splitting and immediate implant placement have been proposed for patients with atrophy of the maxilla in the horizontal dimension. Many lateral augmentation techniques have been successfully adopted for the management of horizontal ridge defects. It is well established that implant placement must be restoratively driven and not bone driven. If one fails to achieve the necessary modifications in bony defects prior to implant placement, then esthetic and/or functional failure is inevitable.Augmentation techniques using autografts or allografts have proven to be successful in highly resorbed ridges, but they have several drawbacks, including invasiveness, the need for an additional donor site, graft resorption, membrane exposure to infection, and delaying of implant placement for grafting maturation. Hence, employing such techniques in moderate horizontal ridge defects (less than 4 mm) is not necessary.

More non-invasive techniques — like ridge expansion and ridge spreading — could be carried out easily, without much trauma to the patient.

Ridge-splitting

When the buccolingual/palatal bone width is 3 mm or greater but less than 6 mm, augmentation of the alveolar ridge using a ridge-splitting and bone expansion technique is a viable option to allow for implant placement within the restorative envelope. The 3 mm of bone should have at least 1 mm of trabecular bone sandwiched between the cortical plates. That will ensure 1.5 mm of bone (cortical and cancellous) on either side of the split ridge and allow the bone to spread and maintain a good vascular perfusion.Several ridge-splitting techniques have been developed in the past few decades, such as the split crest osteotomy and the ridge expansion osteotomy, along with numerous modifications to these techniques.

The criteria for bone expansion and spreading are as follows:

- Ridge width not less than 3 mm.

- Adequate zone of keratinized tissue.

- If there is a combined height and thickness deficiency, the esthetic demands must be minimal.

- Full flaps are not usually necessary if undercuts are minimal.

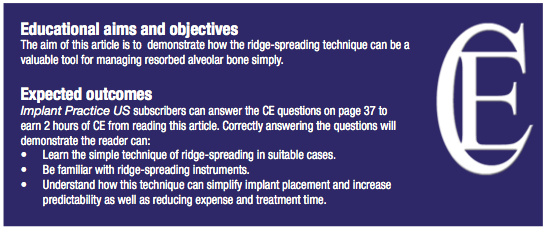

Dr. Hilt Tatum Jr. advocated the ridge-splitting technique back in the 1970s to treat mainly horizontal defects in atrophic maxilla. The technique described by Tatum involved the use of osteotomes of varying thicknesses; these were driven using a mallet to produce gradual splitting and expansion of the alveolar ridge, which allows simultaneous implant placement (Figures 1 to 4).

This technique, employed mainly in the maxilla, relied on the visco-elastic properties of the maxillary bone and required no more than a crestal incision without flap reflection. This allowed the periosteum to remain intact, which maintained the perfusion of the cortical plates and minimized (or eliminated) cortical plate fracture. The author used this technique successfully for many years.

The main disadvantage of this technique is that the mallet application is very disturbing to the patient (unless sedated). In very few cases, some patients reported symptoms of transient vertigo, which resolved within two days. This technique is also very difficult to utilize in the mandible as the cortical plates are denser and more likely to fracture.

Bone spreading

The bone spreading technique (also known as expansion without splitting) involves the insertion of non-cutting tapered bone spreaders in the initial (pilot) osteotomy. This is typically performed at a torque of 50Ncm at an insertion speed of 100rpm with copious irrigation in gradually increasing diameters to the predetermined implantation depth.

There is a lack of adequate research on this technique. However, as it does not involve sharp trauma, in contrast with the technique described by Tatum, and there is less risk of fracture of the cortical plates.

Bone-spreading kits are available from a number of manufacturers. The kit is designed to produce gradual spreading of thin ridges by gradually introducing the “ridge spreaders” in the initial osteotomy, increasing its diameter and allowing the implant to be placed.

Care must be taken with the speed and the torque as described above. If resistance is encountered, the spreading osteotome should be reversed out and the osteotomy recapitulated with a 2-mm drill with copious irrigation and a pumping action to remove bone debris.

A typical spreading kit consists of the following:

- A bone saw

- Expanders

- A ratchet and ratchet adapter

- A bone bur

- A ridge-splitting chisel

The bone saw is used to create the first split in the crestal cortical bone if required as illustrated.

The ridge-splitting chisel is then used to widen the crestal split, thus creating a space for the pilot drill, if needed. The ridge spreaders are of varying diameters and are introduced as described above to produce gradual spreading and widening of the osteotomy diameter to allow the placement of the relevant implant. The ratchet could be used to drive the spreaders if the space is restricted or if resistance is encountered. However, the force should be extremely gradual to avoid overheating of the bone and possible fracture of the cortical plates.

Case study

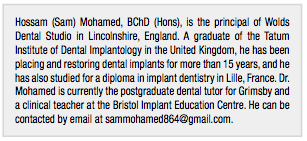

A 35-year-old healthy female non-smoker attended after the loss of the upper left central and lateral incisors, following the failure of her post-retained crowns around 3 years ago. The alveolar ridge displayed no labial undercuts. However, it was around 3.5 mm in width in the coronal 4-5 mm as measured by a ridge mapper (Figure 5).

It was decided to use ridge spreaders to expand and preserve the alveolar bone as opposed to drilling. A flap was raised, and the ridge thickness and topography were examined closely; a cleft in the crest was noted palatally at the UL2.

It was decided to use ridge spreaders to expand and preserve the alveolar bone as opposed to drilling. A flap was raised, and the ridge thickness and topography were examined closely; a cleft in the crest was noted palatally at the UL2.

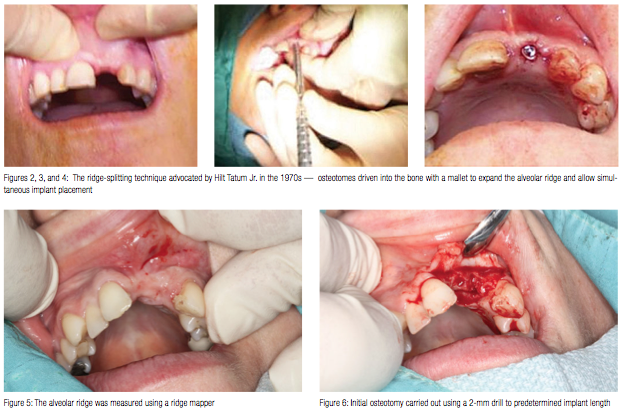

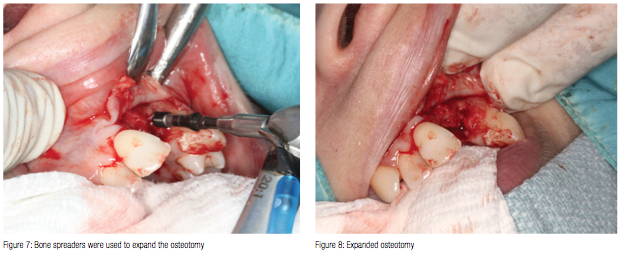

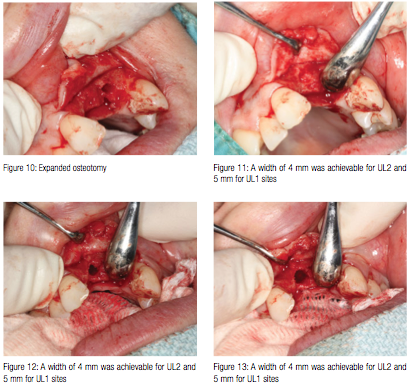

The initial osteotomy was carried out using a 2-mm drill to the predetermined implant length, as the bone density was low (D3). The same process was repeated for UL1 (Figures 5 and 6). The bone spreaders were then used to expand the osteotomy as shown in Figures 7 to 10. A width of 4 mm was easily achievable for UL2 and 5 mm for UL1 sites (Figures 11 to 13).

Conclusion

With the introduction of short and wide implants and the bone spreading technique, many cases with width deficiencies could potentially be treated without grafting.

When bone density is low, spreading rather than drilling is generally more advisable due to the compacting effect of the spreading technique, which helps improve primary stability. Avoiding grafting techniques can help reduce treatment times and complexity — reducing prices while helping predictability and success rates to rise.

References

- Aghaloo TL, Moy PK. Which hard tissue augmentation techniques are the most successful in furnishing bony support for implant placement? Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007;22(suppl):49-70.

- de Wijs FL, Cune MS. Immediate labial contour restoration for improved esthetics: a radiographic study on bone splitting in anterior single-tooth replacement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007;12(5):686-696.

- Flanagan D. Cortical bone spreader osteotome and method for dental implant placement. J Oral Implantol. 2002;28(6):295-296.

- Garber D, Belser UC. Restoration-driven implant placement with restoration-generated site development. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1995;16(8):796-804.

- González-García R, Monje F, Moreno C. Alveolar split osteotomy for the treatment of the severe narrow ridge maxillary atrophy: a modified technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(1):57-64.

- Oh TJ, Shotwell JL, Billy EJ, Wang HL. Effect of flapless implant surgery on soft tissue profile: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2006;77(5):874-882.

- Rammelsberg P, Schmitter M, Gabbert O, Lorenzo Bermejo J, Eiffler C, Schwarz S. Influence of bone augmentation procedures on the short-term prognosis of simultaneously placed implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(10): 1232-1237.

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores