Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists discusses important requisite surgical skills for dental implantologists so they can anticipate complicating factors preoperatively and guide treatment planning and case selection appropriately.

Expected outcomes

Implant Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz online to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

• Identify some needs of hard tissue augmentation.

• Recognize some methods for bone regeneration.

• Realize some fundamental surgical skills for tissue closure.

• Identify some methods of soft tissue augmentation.

• Realize some reasons to pursue more information on lateral sinus augmentation.

Dr. Sean Lan outlines essential implant skills that are important to long-term success.

Dr. Sean Lan offers skills that can help clinicians surmount difficult implant situations

Introduction

I’ll never forget the dreaded “pop” of the anterior nasal spine (ANS) as it greenstick fractured while I was placing a nasopalatine implant to finish off a full arch implant rehabilitation of an atrophic maxilla. Actually, there was no audible sound. But in my head, it was loud, clear, and echoing. My thought was, “What do I do now?” This kind of moment (although few and far between) is sure to happen to anyone doing enough volume and pushing their boundaries (responsibly). It’s a matter of when, not if. And when it happens, we are either prepared for it or we are not. “We don’t rise to the level of our expectations; we fall to the level of our training.” Stay tuned until the end to see how I got myself out of this dilemma.

But first I want to present the main goal of this article, which is to discuss important requisite surgical skills as a dental implantologist — the ones that don’t directly involve “dropping screws in.” These skills are not only important for long term success; they build the foundation of our confidence when Sharpey’s fibers hit the fan. Additionally, being able to anticipate complicating factors pre-operatively can guide clinicians in treatment planning and case selection, which ultimately allows us to push our boundaries responsibly while still providing a high quality of care to our patients. Learning these skills very early on in my career was the only reason I was able to mitigate the problem despite never being in that situation before (re: ANS).

Requisites for success

- Hard tissue augmentation

- Varying levels of augmentation

- Fundamental surgical skills

- Periosteal releasing incision

- Buccal/lingual flap advancement

- Fundamental suturing/membrane stabilization skills

- Soft tissue augmentation

- Free gingival graft (FGG) with apically positioned flap

- Deepithelialized connective tissue graft (CTG) → Subepithelial CTG

- Rotated pedicle flap → Buccal fat pad

- Lateral sinus window (and not necessarily for growing bone)

Like most short-form content, this article is not meant to be a definitive resource. Rather, my goal is to identify key milestones that can help readers accelerate their skills. I hope practitioners of all levels can find something to use in their practices.

Hard tissue augmentation

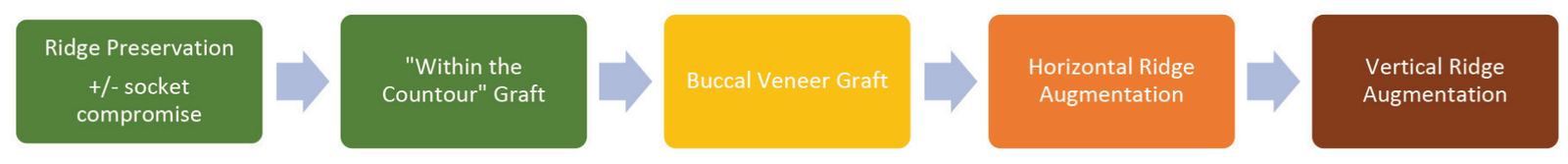

Hard tissue augmentation can be one of the most daunting new skills to learn. There is so much to consider: patient regenerative potential, biomaterial selection, augmentation techniques, etc. However, it is a valuable skillset to add to your repertoire. A 2008 study by Bornstein, et al., found that 51.7% of implants in the study needed additional hard tissue augmentation.1 I have broken down a general progression in this “skill tree” as well as the fundamental skills that can be applied in other situations.

Hard tissue progression

In general, the less contained or “within the contour” of the native bony architecture the graft is, the more difficult it is to regenerate bone. Wang and Boyapati described the four major biologic principles for predictable bone regeneration.3 Dubbed the PASS Principles, these are:

- primary wound closure to ensure undisturbed and uninterrupted wound healing

- angiogenesis to provide necessary blood supply and undifferentiated mesenchymal cells

- space maintenance/creation to facilitate adequate space for bone ingrowth

- stability of wound and implant to induce blood clot formation and uneventful healing events

This is why I recommend starting with ridge preservation of a 4-walled socket. Not every 4-walled socket needs ridge preservation (i.e., it can be an option if you can’t place an immediate implant, need to buy time for patient finances, etc.) but it’s a good place to start. There are many ways to approach this.4 In my studies so far, I have broken down the methods into two main categories: techniques that require primary closure (thus moving the mucogingival Junction [MGJ]) and those that do not. The benefit of leaving the MGJ intact reduces the need for soft tissue grafting later on. Allowing the socket to heal by secondary intention can increase the amount of keratinized tissue (KT) (as long as you have attached KT on both flap margins).

After this factor, predictability and relative ease of technique come next in line. The dense polytetrafluoroethylene (dPTFE) ridge preservation technique is one that fulfills all of these preferences. For more information on this, check out Chapter 3 of Dr. Michael Pikos’ book. (Pikos, MA, Miron RJ. Bone Augmentation in Implant Dentistry: A Step-by-step Guide to Predictable Alveolar Ridge and Sinus Grafting. Quintessence Pub Co.; 2019.) Dr. Pikos has personally taken hundreds of bone cores and found D2 bone at 4 months. dPTFE membrane is more cost effective than a resorbable collagen membrane (RCM). Just pluck it out at 4-6 weeks, and you’ll find complete closure of the site made up of dense connective tissue. Most patients don’t even need topical anesthetic.

Difficulty increases when there are compromises in one or more walls of a socket. There are techniques to deal with these situations, such as the “ice cream cone” technique,6 dPTFE technique for compromised wall sockets (see also, Pikos), and Immediate Dentoalveolar Restoration technique,7 just to name a few. The point is when learning different techniques, there are skills within each technique that we can take and apply to other situations.

Fundamental surgical skills — hard tissue augmentation (Figure 2)

Buccal/lingual flap advancement is necessary for tension-free closure. This is essential in hard tissue augmentation but is a concept that can be applied any time you try to attain primary closure. You begin to train your eye to see where muscle pull is coming from, thus how/where to relieve it. On full-arch implant rehabilitation or “full-arch” cases, a common mistake I’ve noticed is early incision line opening. This usually occurs when the practitioner is trying to achieve primary closure but did not realize the amount of tension on the flaps beforehand. Just because the practitioner can close a flap on the day of surgery doesn’t mean it will stay closed. In addition, scar tissue from previous surgeries can further complicate closure. Prof. Istvan Urban eloquently describes the “periosteo-elastic technique” for flap advancement in Chapter 6 of his landmark textbook (Urban I. Vertical and Horizontal Ridge Augmentation. Quintessence Pub. Co.; 2017). It begins with a gentle periosteal releasing incision (sharp) to open a door past the periosteum into the mucosal layer. Then, it involves semi-sharp and blunt dissection to sever the subperiosteal bundles and stretch the elastic fibers, respectively. This skill transfers well to learning split thickness flap preparation for soft tissue work.

Once tension-free flaps are established, how can they be closed for hard tissue augmentation? The first layer in a double layered closure consists of horizontal/vertical mattress sutures. These tension-relieving sutures reduce/eliminate remaining tension at the margins and evert them. Then, the second layer consists of simple interrupted/continuous sutures to finalize the closure (Figure 4).

Next, when placing a barrier membrane, how do we stabilize it? This is where the art and creativity come into play. The most approachable techniques to start with are the periosteal vertical mattress,8 poncho technique, and double membrane technique.9 Poncho technique is quite simple and involves cutting a “X” or a small hole in the membrane (or PRF slug) and threading an implant abutment through it (Figure 5). Transosseous sutures involve creating an osteotomy in existing bony architecture with a small diameter bur (e.g., 701 bur) through which a suture can be passed and fixated. An osteotomy can be created through a single cortex, or both. Some use case examples are to apically position flaps for a mandibular overdenture and creating fixation points to suture a resorbable collagen membrane to while repairing a buccal plate fracture (Figure 6).

One of my favorite techniques is the membrane-tacking suture which is involved in the “SauFRa Technique” described by Kamat in 2020.10 It is a bit more technique-sensitive, but essentially it is used to stabilize the membrane along the apical and coronal edges. Tacking sutures are placed along the apical membrane edge to the apical periosteum and along the coronal membrane edge to the palatal/lingual flap. It is combined with periosteal vertical mattress sutures on the lateral extent of the membrane to prevent lateral extrusion of graft material. To put it simply, you are making a “Hot Pocket” to contain your graft material (Figure 7). So go on and get creative! There are many techniques to stabilize a membrane such as Ribroast,11 Lasso,12 and using tacks as fixation points for sutures.13

Soft tissue augmentation

This is another daunting topic to tackle; however, it is crucial to have these skills for long term maintenance of dental implants. While the maxilla has an abundance of attached KT, the mandible lacks such supply. Add in loss of vestibular depth, and a seemingly straightforward mandibular overdenture just got harder to manage. In my opinion, the fundamental techniques to start with are the free gingival graft (FGG) and apically positioned flap (APF). These will require the clinician to become proficient in split thickness dissection, which is used for the FGG harvest and preparation of the recipient bed and APF. This will be useful to increase attached KT on the buccal (and sometimes lingual) of the implants. When KT needs to be increased on both sides, this is more often done in a two-stage approach.

The next natural progression is the connective tissue graft (CTG). There are two main types of harvest: the deepithelialized CTG and the sub-epithelialized CTG. De-epithelialized CTG (DFGG) is harvested in a similar fashion as an FGG and followed with subsequent removal of the epithelial layer with a blade. Other methods of de-epithelialization include using a round diamond bur before taking the harvest. Subepithelial CTG (SECTG) involves leaving the epithelial layer intact and harvesting only the connective tissue layer. By nature, DFGG will take a more superficial portion of the CT layer while SECTG will take a deeper portion of the CT layer. There is limited but growing evidence comparing the two methods, but results have shown that there is no significant difference in pain (which is one of the main talking points favoring SECTG). Some studies also show that the deeper the harvest is, the more pain.14-15 In terms of performance, some studies show that DFGG outperforms SECTG in terms of increase in soft tissue thickness. The theory is that the deeper layers of CT have a higher percentage of fatty/glandular tissue instead of dense CT that we are looking for. Clinicians like Dr. Pat Allen and Giovanni Zucchelli advocate for the DFGG whereas Drs. Hurzeler and Zuhr mention that they prefer the SECTG at the time of their textbook was published in 2012. Either way, the DFGG is more approachable technique-wise, so I would recommend to start there.

Finally, we have the rotated pedicle flap in the lineup of high-yield fundamental soft tissue skills. This is a useful tool to have to increase tissue thickness around implants and to repair small-to-medium sized oroantral communications (OAC) to spare the buccal fat pad.16 It can be secured in many ways, so use your creativity and the tools you have from your membrane stabilization toolbox! You can suture directly to the flap, periosteum, or even create a transosseous purchase point.

Putting all these fundamental soft tissue skills together, you will be armed with the tools to perform more challenging procedures, like the classic vestibuloplasty via FGG and APF.

Lateral sinus augmentation

While it is important to know how to perform a lateral sinus augmentation, my main goal for pursuing this skill early on was more so to be comfortable working in the sinus. This greatly reduces the stress of displacing a tooth/root/implant into the sinus. The sinus membrane repair technique is also a great tool to have in the toolbox, as it gives you another way of looking at repairing the membrane while minimizing cutting off blood supply from the bony walls.17 In his article, Dr. Michael Pikos describes his modified technique using a slow-resorbing type I collagen membrane for repair of large and complete sinus membrane perforations. The membrane creates space facilitating graft placement. Also, “The biocompatibility and semirigid structural integrity of this membrane, along with external tack fixation, allows for optimal membrane stabilization and maintenance.” As the clinician’s skills advance, these skills can be applied to lifting the sinus membrane for a trans-sinus implant or a pterygoid implant that needs to traverse the sinus.

Putting it all together

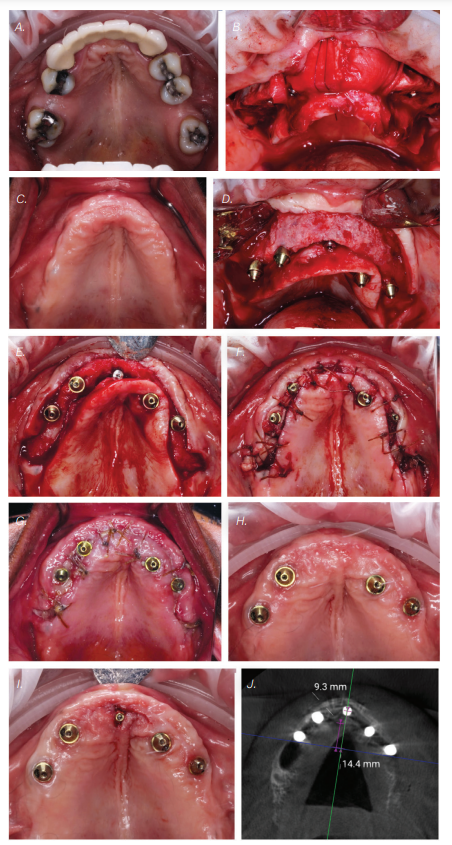

Finally, let’s revisit the opening scenario: how did I end up choosing to manage the greenstick-fractured ANS? My training certainly came in handy that day. This stressful event is evidenced by the fact that I barely managed two clinical photos that day. The patient was planned for a maxillary implant-fixed complete denture. She had an atrophic maxilla with anteriorly and inferiorly pneumatized sinuses. However, with the use of a nasopalatine implant19-20 anteriorly, I was able to achieve adequate AP spread. It was the fifth and last implant I had planned for this case. I fully prepped the osteotomy as the atrophic anterior maxilla lacks sufficient elasticity from trabecular bone. As I placed the implant and was finishing with my torque wrench around 40 Ncm, I felt and saw the ANS greenstick fracture. Since I am not trained on reconstruction plates to reduce bony fractures, I had to think fast. I decided to combine concepts from Urban’s “Sausage” technique as well as membrane tacking sutures from the Kamat’s “SauFRa” technique to stabilize the graft and the ANS. Essentially, this turned into an “unintentional” ridge split.

Conclusion

Learning certain fundamental skills early on in your implant career can improve your treatment planning, manage more complications, and ultimately boost your confidence when pushing your boundaries.

To budding implantologists — are you ready to take the next step in elevating your skills? Even if you want to stay with the basics of International Team for Implantology Straightforward Advanced Complex (classification system) (ITI SAC) straightforward cases, thinking about these issues can help you identify and refer cases that can be more complex than it seems on the surface. To my more experienced colleagues — let me know your thoughts! What other high yield skills can one benefit from learning early on?

Increasing essential implant skills can mean knowing the guidelines for using CBCT for implants. Read this article by Dr. Johan Hartshorne on applications of CBCT here: https://implantpracticeus.com/archived-ce/essential-guidelines-for-using-cbct-in-implant-dentistry-clinical-considerations-part-2/

References

- Bornstein MM, Halbritter S, Harnisch H, Weber HP, Buser D. A retrospective analysis of patients referred for implant placement to a specialty clinic: indications, surgical procedures, and early failures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2008 Nov-Dec;23(6):1109-1116.

- Kamat SM, Khandeparker RV, Akkara F, Dhupar V, Mysore A. SauFRa Technique for the Fixation of Resorbable Membranes in Horizontal Guided Bone Regeneration: A Technical Report. J Oral Implantol. 2020 Dec 1;46(6):609-613.

- Wang HL, Boyapati L. “PASS” principles for predictable bone regeneration. Implant Dent. 2006 Mar;15(1):8-17.

- Horowitz R, Holtzclaw D, Rosen PS. A review on alveolar ridge preservation following tooth extraction. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2012 Sep;12(3 Suppl):149-160.

- Luongo R, Tallarico M, Canciani E, Graziano D, Dellavia C, Gargari M, Ceruso FM, Melodia D, Canullo L. Histomorphometry of Bone after Intentionally Exposed Non-Resorbable d-PTFE Membrane or Guided Bone Regeneration for the Treatment of Post-Extractive Alveolar Bone Defects with Implant-Supported Restorations: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Materials (Basel). 2022 Aug 24;15(17):5838.

- Tan-Chu JH, Tuminelli FJ, Kurtz KS, Tarnow DP. Analysis of buccolingual dimensional changes of the extraction socket using the “ice cream cone” flapless grafting technique. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2014 May-Jun;34(3):399-403.

- da Rosa JC, Rosa AC, da Rosa DM, Zardo CM. Immediate Dentoalveolar Restoration of compromised sockets: a novel technique. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2013 Autumn;8(3):432-443.

- Urban IA, Lozada JL, Wessing B, Suárez-López del Amo F, Wang HL. Vertical Bone Grafting and Periosteal Vertical Mattress Suture for the Fixation of Resorbable Membranes and Stabilization of Particulate Grafts in Horizontal Guided Bone Regeneration to Achieve More Predictable Results: A Technical Report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2016 Mar-Apr;36(2):153-159.

- Bornstein MM, Heynen G, Bosshardt DD, Buser D. Effect of two bioabsorbable barrier membranes on bone regeneration of standardized defects in calvarial bone: a comparative histomorphometric study in pigs. J Periodontol. 2009 Aug;80(8):1289-1299.

- Kamat SM, Khandeparker RV, Akkara F, Dhupar V, Mysore A. SauFRa Technique for the Fixation of Resorbable Membranes in Horizontal Guided Bone Regeneration: A Technical Report. J Oral Implantol. 2020 Dec 1;46(6):609-613.

- Fien M, Puterman I, Mesquida J, Bauza G, Ginebreda I. The Ribroast Technique™: An Alternative Method to Stabilize a Resorbable Collagen Membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2023 Jul-Aug;44(7):408-414.

- Neiva R, Duarte W, Tanello B, Silva F. “LASSO GBR – rationale, technique, and long-term results.” Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2018;29(S17): 447.

- Fien M, Puterman I, Mesquida J, Ginebreda I, Bauza G. Guided Bone Regeneration: Novel Use of Fixation Screws as an Alternative to Using the Buccoapical Periosteum for Membrane Stabilization With Sutures—Two Case Reports. Compendium. Feb. 2024;45(2). https://www.aegisdentalnetwork.com/cced/2024/02/guided-bone-regeneration-novel-use-of-fixation-screws-as-an-alternative-to-using-the-buccoapical-periosteum-for-membrane-stabilization-with-sutures-two-case-reports. Accessed October 23, 2024.

- Zucchelli G, Mele M, Stefanini M, Mazzotti C, Marzadori M, Montebugnoli L, de Sanctis M. Patient morbidity and root coverage outcome after subepithelial connective tissue and de-epithelialized grafts: a comparative randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2010 Aug 1;37(8):728-738.

- Tavelli L, Ravidà A, Lin GH, Del Amo FS, Tattan M, Wang HL. Comparison between Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft and De-epithelialized Gingival Graft: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2019 Apr 1;21(2):82-96.

- El Chaar E, Oshman S, Cicero G, Castano A, Dinoi C, Soltani L, Lee YN. Soft Tissue Closure of Grafted Extraction Sockets in the Anterior Maxilla: A Modified Palatal Pedicle Connective Tissue Flap Technique. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2017 Jan/Feb;37(1):99-107.

- Pikos MA. Maxillary sinus membrane repair: update on technique for large and complete perforations. Implant Dent. 2008 Mar;17(1):24-31.

- International Team for Implantology. “SAC Assessment Tool.” ITI, www.iti.org/tools/sac-assessment-tool. Accessed October 1, 2024.

- Peñarrocha M, Carrillo C, Uribe R, García B. The nasopalatine canal as an anatomic buttress for implant placement in the severely atrophic maxilla: a pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009 Sep-Oct;24(5):936-942.

- Peñarrocha D, Candel E, Guirado JL, Canullo L, Peñarrocha M. Implants placed in the nasopalatine canal to rehabilitate severely atrophic maxillae: a retrospective study with long follow-up. J Oral Implantol. 2014 Dec;40(6):699-706.

Stay Relevant With Implant Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and mores

Sean Lan is a dedicated practitioner based in Stockbridge, Georgia, serving the surrounding areas with a passion for dental implantology and dentoalveolar surgery. After completing his undergraduate and dental degrees at the University of Florida, Dr. Lan embarked on a 1-year AEGD residency, solidifying his interest in dental surgery. He further honed his skills by completing in the AFPDS Implant program with the USAF Department of Prosthodontics and dedicating hundreds of hours reading literature and textbooks. Currently, Dr. Lan works with a nationwide DSO focused on full arch implantology where he serves as a mentor to his peers in and out of the group. You can see more of his work on his Instagram page @DrSeanLan, where his mission is to “Make Reading Sexy Again.”

Sean Lan is a dedicated practitioner based in Stockbridge, Georgia, serving the surrounding areas with a passion for dental implantology and dentoalveolar surgery. After completing his undergraduate and dental degrees at the University of Florida, Dr. Lan embarked on a 1-year AEGD residency, solidifying his interest in dental surgery. He further honed his skills by completing in the AFPDS Implant program with the USAF Department of Prosthodontics and dedicating hundreds of hours reading literature and textbooks. Currently, Dr. Lan works with a nationwide DSO focused on full arch implantology where he serves as a mentor to his peers in and out of the group. You can see more of his work on his Instagram page @DrSeanLan, where his mission is to “Make Reading Sexy Again.”