Dr. Maher Kemmoona illustrates how to achieve predictable, lasting, and esthetic outcomes with dental implant therapy regardless of whether it’s a simple or complex restoration

Any dental therapy should aim at restoring a patient’s dental occlusion. This is not always the case, nor is it always the patient’s desire. And why would it be? Our patients are not dentists after all; they do not share our understanding of oral health, the need for sufficient number of teeth in good occlusal relationship to each other, the knowledge of interrelationship of chronic oral disease, such as periodontitis, and general well-being.

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to offer suggestions on achieving predictable, lasting, and esthetic outcomes with dental implant therapy.

Expected outcomes

Implant Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify a defined protocol to derive the most appropriate treatment options for presentation to patients.

- Identify questions to ask patients regarding the etiology of the destruction of their dentition.

- Realize some contraindications for dental implant therapy.

- Recognize the possibility of reducing risk by implementing a sequential in-depth examination of the patient.

- Recognize, through viewing case studies, various treatment plans that illustrate the need for adequate data collection prior to treatment.

Not surprisingly, we see many patients in the middle-aged group who have a significantly destructed dentition, possibly due to caries with further complexities such as advanced non-carious tooth surface loss due to factors such as erosion and wear, often resulting in the lack of an adequate posterior occlusal support.

These patients often feel they have had a lot of dental treatment in the past, and truthfully, they often have; but often enough the main reasons for the destruction of their dentition over extensive periods of time have never been addressed appropriately.

Prevention

Treatment planning for simple and complex rehabilitations takes time and a certain knowledge bank; there is a need for in-depth examination of the patient. Most of all, we ought to establish why patients find themselves in the dilemma in the first place in order to prevent the story from repeating itself after treatment.

Why should the treatment planning for dental implants differ from those previously mentioned? In order to prescribe the necessary therapy, dentists ought to follow a defined protocol — a repeated sequence in examining the patient. This subsequently allows clinicians to derive the most appropriate treatment options for presentation to patients.

Unfortunately, it is here that we as dentists may encounter resistance on our patients’ behalf. Often they only sought our advice in regard to a problem with a single or just a few teeth and are now overwhelmed with the depth of the deeper problem. This frequently becomes an ethical dilemma in therapy, and the resulting questions are not easily answered.

Taking a medical-scientific point of view, to repeat a sequential pattern in the dental record taking, an accurate physical and social history, as well as an in-depth physical examination, has proven itself.

In complex cases, this should be augmented by specific laboratory data collection and analysis, such as a facebow transfer of jaw position followed by a simple wax-up or setup of denture teeth. This will assist in planning and may show up problems that could likely be encountered later along the way in treatment. Most of all, it will allow dentists to prescribe treatment based on reproducible data derived from the different aspects of the examination — it appears to be the safest way in coming to a diagnosis and a therapeutic plan.

When determining the etiology of the destruction of our patients’ dentition, it can help to ask patients simple questions, such as:

- When did problems begin?

- Where did problems begin?

- Has the patient had any treatment for the problems?

- Has previous treatment affected the patient’s condition?

Answering these questions will allow us to see if the patients are engaged in treatment, have understood the relevance of our findings, and taken aboard their own role in the making of the dental problems apparent. Can we ethically engage in complex therapy with patients who have not taken responsibility for their own health — especially when it comes to dental implant therapy, which for most of its course remains elective treatment?

A good option?

Most of the existing research on dental implant therapy and the outcome relates to healthy individuals — maybe with the exception of diabetes and periodontitis. At the same time, very little has been published on the long-term survival of dental implants in patients who are susceptible to aggressive periodontal disease.

Given the prevalence of chronic diseases and an aging population, we should be cautious in treatment prescription and reflect on the true need for dental implants in patients.

Currently, we accept the following absolute contraindications for dental implant therapy in a dental practice setting (Hwang, Wang, 2006):

- Recent myocardial infarction and cerebro-vascular accident, heart valve replacement

- Recent immunosuppressive therapy

- Bleeding disorders

- Patients receiving active treatment of malignant tumors

- Drug abuse

- Certain psychiatric illnesses

- Intravenous bisphosphonate use

To a lesser degree, we have scientific support for the relative contraindications to implant therapy in practice, and these mirror very much what is accepted to be good practice for oral surgery procedures under these circumstances (Hwang, Wang, 2007).

We ought to respect illnesses that impair the normal healing cascade and as such have the potential to worsen surgical success. Certain disorders, when well controlled, allow implant survival rates that match those in healthy patients — among these we find factors such as osteoporosis, smoking, diabetes, positive interleukin-1 genotype, HIV, cardiovascular disease, and hypothyroidism. Generally speaking, we find higher rates of immediate postoperative complications, significantly increased levels of long-term complications, e.g., mucositis, peri-implantitis, and implant loss, in smoking patients. To date, research has not been able to improve definitive treatment modalities to rectify these on a reproducible level.

It is suggested that in diabetic patients, complications arising during dental implant treatment may result from early disruption of adequate bone healing in the first few weeks after surgery; these complications may even be important in long-term failure, but research into the exact mechanisms at play here is still ongoing.

If we can control co-factors such as poor oral hygiene, smoking, unstable periodontal status, a stabilization of glycemic control (HbA1c at around 7%) in diabetic patients, we may achieve a good outcome for therapy. In these cases, it is of utmost importance to take preventive measures against infection immediately post-surgery.

Looking at the periodontal patient, it appears that, short-term, similar levels of implant success/survival can be expected. This changes significantly in the long-term, and there is clear evidence of a higher rate of complications developing, including mucositis and peri-implantitis, and, worst case, even the loss of implant integration. Unfortunately, there is little medium- or long-term scientific data present on implant success/survival in patients who have been treated for aggressive periodontitis, which makes this a higher risk cohort of patients to treat in practice.

Sequence of examination

One way to assess the issues outlined previously, and in order to reduce risk during therapy, is the implementation of a sequential in-depth examination of the patient who desires to undergo dental implant treatment. During this examination, it is advisable to work through the following points:

- Evaluation of relevant medical and social history

- Assessment of oral mucosal tissues in form, function texture, including salivary flow for any pathological changes

- Recording of remaining teeth and their restorative/endodontic status

- Determining the occlusion reflected from both a dental and skeletal perspective

- Screening or, if necessary, a full periodontal examination

- Reflection on mobility of remaining teeth to determine whether this is due to traumatic occlusion or loss of periodontal support

- Evaluation of amount of attached gingiva present, including phenotype of gingiva: thin or thick

- Palpation of site — with increasing experience, a lot of information can be gained easily and noninvasively

- Radiographic examination — including periapical radiographs, OPG, or 3D scans.

The relative findings can be brought into perspective with the patient’s overall wishes, and this should always allow to define a common ground to agree on a treatment path for the patient.

Case 1

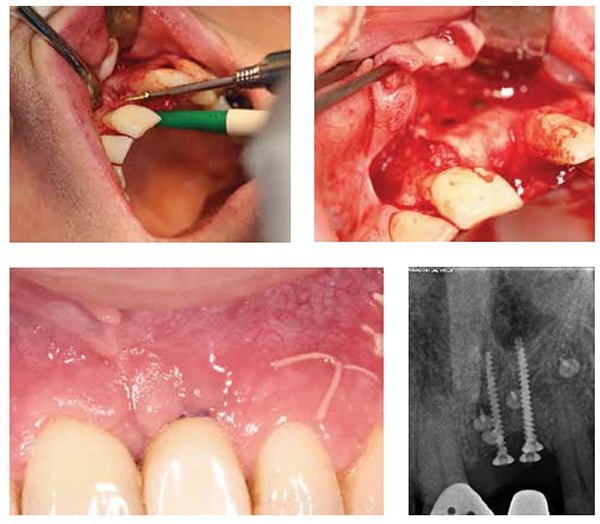

The first case presented is a result of trauma due to a motor accident in which a lower and upper incisor were avulsed. The upper incisor was replanted, but the tooth became non-vital over time, and the infection meant loss of both hard and soft tissue. The patient suffered significant other traumatic injuries in this accident.

Both the dental clinical examination and radiographic evaluation revealed a three-dimensional hard and soft tissue defect at the tooth UL1. Extraction of the tooth was necessary, and the size of the defect resulted in a vague prognosis for implant therapy at a later stage. These findings were discussed with the patient, and the resulting treatment plan included the need for a 3D bone graft as well as soft tissue augmentation in order to provide a fixed dental restoration. The patient was in his mid-30s, was a non-smoker, and his medical history was clear. He had fully recovered from the injuries of previous trauma at this stage.

Figure 2 shows the resulting defect after tooth removal. At this time, a maxillary frenectomy had been completed to ensure tension-free closure after the grafting procedure. The bone graft was completed using titanium pins and bone block screws in addition to a mix of autogenous bone and bovine-derived xenograft substitute material.

Healing was uneventful. Six months after bone augmentation, a narrow platform dental implant as well as a connective tissue graft could be placed, which ultimately allowed for repair of the previous 3D defect in this case. The intraoperative sequence of the bone graft procedure and the resulting post-

operative view after implantation are presented in Figure 3.

Case 2

The second clinical case was significantly dependent on the initial planning procedure described previously. This patient had a complex medical history and was taking several different types of medication for chronic diseases.

The existing long-span Maryland bridge had successfully restored the occlusion for almost 20 years. At the time of its failure, there were multiple unrestorable teeth present, and the distribution of the remaining restorable teeth was not favorable to retaining them (Figure 4).

In this case, a set of study models was mounted after facebow transfer and a partial setup of denture teeth utilized to assure the correct vertical treatment position and esthetics prior to any treatment being provided. The nine remaining maxillary teeth were extracted and seven tapered dental implants placed immediately for the patient. The same afternoon, a temporary bridge was fitted, screw-retained to the five implants that showed the highest insertion torque on implantation.

The initial diagnostic setup allowed for a provision of a surgical guide to assure parallel implant placement. The same setup was used by the lab in the transition to the same-day temporary acrylic bridge.

Implant-level silicone impressions were taken immediately after insertion of the dental implants, and these were sent with an accurate bite registration to the dental lab. The transition from an acrylic denture derived from the previous diagnostic setup to the transitional acrylic bridge was achieved in just a few hours. This allowed the patient to leave the practice the same evening with a fixed temporary implant-supported bridge. The accuracy of fit can be related to the amount of data collected prior to treatment and is, for most cases, reproducible.

Six months after insertion, the implants are integrated, and the patient is due to progress into the final restoration planned as a titanium acrylic hybrid bridge. Once again, the initial diagnostic setup will aid in the laboratory procedures necessary, providing reference to jaw relationship and tooth position.

Cases 3 and 4

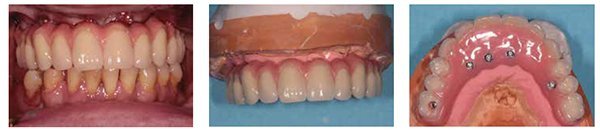

Figures 8 to 10 show a series of complex implant cases. These include the treatment of severely atrophic maxillary arches with implant reconstructions, leading to a good esthetic and functional outcome (Figures 8-9).

In all the cases, the patients had lost their natural dentition due to progressive periodontal disease, resulting in having limited bone available. A combination of appropriate diagnostic work-up and surgical pre-planning allowed for a good esthetic and functional outcome despite the limitations given at the outset of therapy.

Figure 10 illustrates both the treatment of congenitally missing lateral incisors after orthodontic treatment and a case of combined surgical/prosthetic retreatment of previously apicetomized teeth, which had to be extracted. The final implant crowns were screw-retained. This can be difficult due to the angulation of implant placement. Despite the lack of adequate bone at the outset of therapy, the goal was achieved.

Conclusion

In all the cases presented, the previously described assessment sequence was followed, and very simple and cost-effective data analysis, including diagnostic setups/wax-ups, resulted in a predictable outcome of therapy, fulfilling the patients’ expectations. None of these cases were simple to start with, but the relevant data collection and analysis allowed for a reproducible outcome.

The case studies illustrating various treatment scenarios hopefully underpin the need for adequate data collection prior to treatment. Dental implant therapy has long moved from hoping to see the titanium screw integrate; very complex treatment is now predictably possible, even for patients with a complex history.

We do need to understand the limitations in order to assess these cases appropriately. Only by collecting the right information can a treatment plan be put together that will ensure a predictable, lasting, and esthetic outcome to dental implant therapy.

References

- Hwang D, Wang HL. Medical contraindications to implant therapy: part I: absolute contraindications. Implant Dent. 2006;15(4):353-60.

- Hwang D, Wang HL. Medical contraindications to implant therapy: part II: relative contraindications. Implant Dent. 2007;16(1):13-23.

Maher Kemmoona, M. Dent. Ch (Perio), specializes in the provision of complex dental care and has practiced exclusively in implant dentistry and periodontology since completing the postgraduate course in periodontology at Trinity College Dublin in 2007. Maher qualified at the University of Erlangen-Nurnberg, Germany, in 1999 and worked both as a general dentist and in perio-prosthetic specialist practice before returning to Ireland in 2002. He has a keen interest in the management of peri-implantitis and failing implant prosthetics.

Maher Kemmoona, M. Dent. Ch (Perio), specializes in the provision of complex dental care and has practiced exclusively in implant dentistry and periodontology since completing the postgraduate course in periodontology at Trinity College Dublin in 2007. Maher qualified at the University of Erlangen-Nurnberg, Germany, in 1999 and worked both as a general dentist and in perio-prosthetic specialist practice before returning to Ireland in 2002. He has a keen interest in the management of peri-implantitis and failing implant prosthetics.